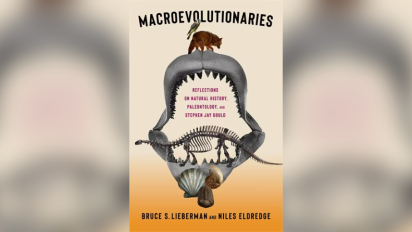

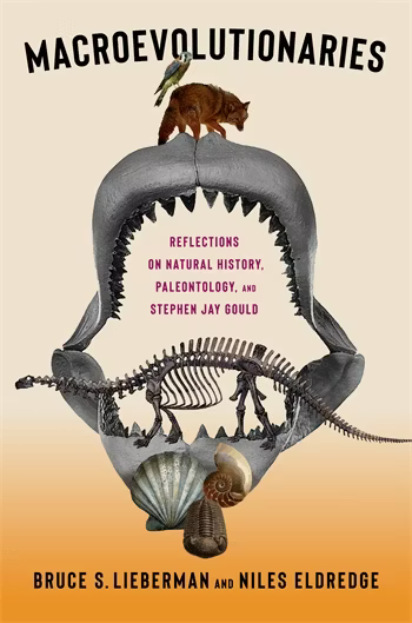

[Review] Macroevolutionaries: Reflections on Natural History, Paleontology, and Stephen Jay Gould

Macroevolutionaries: Reflections on Natural History, Paleontology, and Stephen Jay Gould "will appeal to professionals in paleontology, biology, and the history of science as well as to natural history buffs and especially to fans of Stephen Jay Gould," our reviewer writes.

I miss Stephen Jay Gould. When I was his graduate student in the mid- to late 1970s, Steve gave me a signed copy of Ever Since Darwin, the first book that compiled his Natural History essays. I eagerly devoured it and subsequent collections of his essays and used them frequently in my 37 years of teaching paleontology. Steve continued to crank out these essays, and ten books compiling them, in sickness and in health … until he didn’t. In May 2002, he surrendered to cancer, leaving a huge gap in the communication of evolutionary concepts to general audiences.

Macroevolutionaries: Reflections on Natural History, Paleontology, and Stephen Jay Gould helps fill this void. Bruce Lieberman and Niles Eldredge coauthored Macroevolutionaries in part to pay homage to Steve and honor his legacy. Steve was Lieberman’s undergraduate advisor; Steve and Eldredge met as students at Columbia in the 1960s and later collaborated on the groundbreaking papers on punctuated equilibria (1972–1977) that irrevocably altered evolutionary thinking. As colleagues and friends of Steve who knew him well, Lieberman and Eldredge share anecdotes and impressions of him both as a brilliant thinker and as a kind and generous person, and they give insight into the factors that molded Steve’s thought.

Macroevolutionaries: Reflections on Natural History, Paleontology, and Stephen Jay Gould helps fill this void. Bruce Lieberman and Niles Eldredge coauthored Macroevolutionaries in part to pay homage to Steve and honor his legacy. Steve was Lieberman’s undergraduate advisor; Steve and Eldredge met as students at Columbia in the 1960s and later collaborated on the groundbreaking papers on punctuated equilibria (1972–1977) that irrevocably altered evolutionary thinking. As colleagues and friends of Steve who knew him well, Lieberman and Eldredge share anecdotes and impressions of him both as a brilliant thinker and as a kind and generous person, and they give insight into the factors that molded Steve’s thought.

Macroevolutionaries (the title is derived from “macroevolution,” which they describe as the major features of evolution, e.g., the origin and extinction of species) was inspired by Gould’s Natural History essays. Lieberman and Eldredge reflect on Gould’s numerous contributions to evolutionary and paleontological thought and discuss many of his favorite topics, such as punctuated equilibria (the revolutionary but now generally supported idea that most evolution is concentrated during episodes of species origination that are brief compared to the species’ duration); the role of constraints and contingency, which stresses the effect of lineage histories on evolutionary outcomes; the importance of mass extinctions in evolutionary history; the nature of historical sciences; and the role of adaptation in evolution.

The style of the 13 essays comprising Macroevolutionaries is reminiscent of Gould’s work. Like Gould, Lieberman and Eldredge excel at discussing complicated evolutionary concepts in terms accessible to a general audience. They provide numerous analogies to clarify these concepts, for instance drawing connections between the volatility of the stock market and susceptibility of groups of organisms to mass extinctions. Like Gould’s essays, theirs are steeped in history; they provide perspectives on many historical and contemporary figures in geology, paleontology, and evolutionary biology. Darwin is discussed extensively, of course, but they also bring to life other personages less well known outside of paleontology, such as James Hall, Norman Newell, and Carl Dunbar. Several essays highlight work by Elisabeth Vrba, one of the “Three Musketeers” (along with Eldredge and Gould), whom Gould mentioned in the dedication of his massive final volume, The Structure of Evolutionary Theory. They also challenge misconceptions about historical figures, defending the often-disparaged Lamarck, who influenced Darwin’s views, and skewering Charles Lyell (one of my personal heroes, sigh!) for plagiarism.

Lieberman and Eldredge also aren’t afraid to poke fun at themselves, which makes for entertaining reading. I’ve known them both for years — Eldredge since the day after Thanksgiving in 1976 when he kindly met me in his office (with his toddler son), at Steve’s behest, to discuss plans for my PhD thesis testing punctuated equilibria. But I didn’t know, for example, that Lieberman has no sense of fashion or that he was a fan of Beavis and Butthead.

I don’t agree with all their assessments. For instance, I see ecological factors as more important in evolution than they do, and they include some rather speculative (but admittedly fun) ideas, e.g., the hypothesis that a supernova caused the extinction of the enormous shark Carcharocles megalodon. I think some chapters will be more meaningful to other paleontologists than to the public, such as chapter seven on Norman Newell and his work on mass extinctions. Some chapters meander a bit (e.g., chapter four, which discusses Gould’s views of “time’s arrow, time’s cycle”) or seem disjointed (chapter seven on Newell), and some digressions function primarily to show off Lieberman and Eldredge’s cultural knowledge. But the cultural references are quite fun and diverse, from philosophy (e.g., Kant, Hume, Bertrand Russell) to literature, music (especially jazz), sports, TV, movies, and pizza. Chris Rock, William Shatner, Nicolas Cage, and Jason Statham, among others, make appearances.

The writing is lively and entertaining, with puns and plays on words, and I found Macroevolutionaries to be an enjoyable read as well as informative. Although I got to know Steve well when I was his student, I still learned much from Macroevolutionaries — about Steve, other paleontological/evolutionary luminaries, natural history, and evolution. The book will appeal to professionals in paleontology, biology, and the history of science as well as to natural history buffs and especially to fans of Stephen Jay Gould. Macroevolutionaries continues Steve’s legacy and helps fill the gap left by his untimely death.

Macroevolutionaries: Reflections on Natural History, Paleontology, and Stephen Jay Gould

Authors: Bruce S. Lieberman and Niles Eldredge

Publisher: Columbia University Press