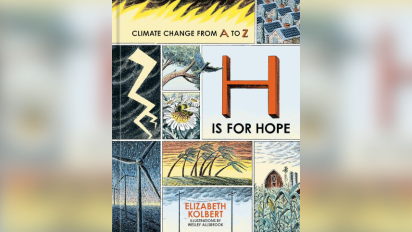

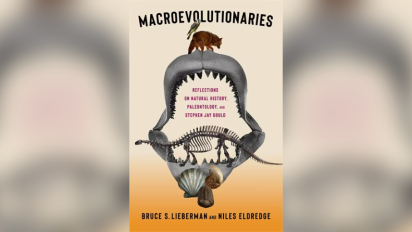

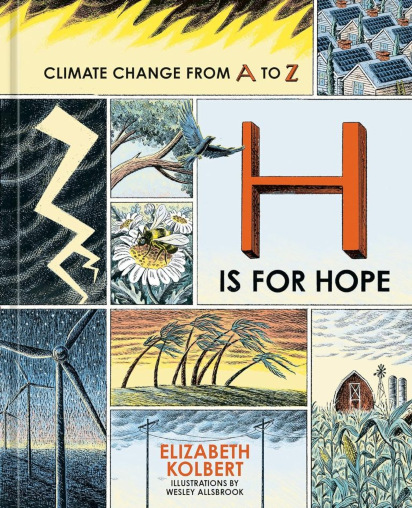

[Review] H is for Hope: Climate Change from A to Z

"Kolbert’s nuanced and visually compelling story of climate change offers readers a glimmer of possibility while also showing the very real obstacles we’re up against," our reviewer writes of H is for Hope: Climate Change from A to Z.

As I write these words in late September 2024, the southeastern United States is reeling from the catastrophic impacts of Hurricane Helene. On the other side of the world, massive flooding and landslides have devastated Kathmandu, Nepal. Record high temperatures continue to be set in the American Southwest, on the heels of the hottest summer ever recorded, and likely the hottest year. It’s hard to feel hope when the climate seems off the rails.

We all could use some reassurance in times such as these, and Elizabeth Kolbert’s book, H is for Hope: Climate Change from A to Z, provides many reasons for cautious optimism.“Go looking for hopeful climate stories and they turn up everywhere,” the author notes in the titular chapter (page 52). But Kolbert is no Pollyanna. Her series of 26 essays — one for each letter of the alphabet — offers a sober look at the daunting challenges facing humanity in a rapidly warming world.

We all could use some reassurance in times such as these, and Elizabeth Kolbert’s book, H is for Hope: Climate Change from A to Z, provides many reasons for cautious optimism.“Go looking for hopeful climate stories and they turn up everywhere,” the author notes in the titular chapter (page 52). But Kolbert is no Pollyanna. Her series of 26 essays — one for each letter of the alphabet — offers a sober look at the daunting challenges facing humanity in a rapidly warming world.

H is for Hope, which originally appeared in The New Yorker in 2022, is accompanied by Wesley Allsbrook’s beautiful and evocative ink illustrations. The text and art combine to create the feeling of a graphic novel or picture book.

In the first few chapters, Kolbert takes readers on a breakneck journey through the last 130 years, from the late-19th-century Swedish physicist Svante Arrhenius’s discovery of carbon dioxide’s impact on global temperatures to Greta Thunberg (another world-renowned Swede) delivering her now infamous “blah, blah, blah” speech in 2021. In the intervening years, climate change became recognized as a significant problem — one that world leaders tried to address in Rio in 1992, then in Kyoto in 1997, and again in Paris in 2015, each time with a renewed sense of optimism and resolve.

Kolbert suggests that their confidence was unwarranted. She writes, “Nevertheless, emissions continued to rise. In the past thirty years, humans have added as much CO2 to the atmosphere as they did in the previous thirty thousand” (page 19). She points to capitalism as the driving force behind these changes, with resulting human and ecological costs reflective of a glitch of the system, a characteristic of the system itself, or a challenge humanity may not even be equipped to solve.

As if reading the reader’s mind, Kolbert admonishes, “Despair is unproductive. It is also a sin” (pages 30–31). Turning the page, she begins anew. “Let’s try again. This time with feeling” (page 34).

In the next 10 chapters, Kolbert catalogs the myriad ways that progress is happening, despite the steady rise in emissions. She documents the rapid expansion and cheapness of renewable energy, innovations in electric airplanes, development of green concrete, promise of batteries powered by rusting iron, historic investments of the Inflation Reduction Act, job opportunities made possible by the green economy, and the potential to address global climate injustices through leapfrogging and funding from developed nations.

It is often said that we have the solutions to address climate change. Many would further argue that communicating these to the broader public is itself a solution. Kolbert writes, “Positive stories can also become self-fulfilling. People who believe in a brighter future are more likely to put in the effort required to achieve it. When they put in that effort, they make discoveries that hasten progress” (page 82).

But H is for Hope ultimately resists the pressure to communicate only optimism. In the chapter O (for Objections), Kolbert admits, “Everything I have written, from ‘Despair’ onward, is vulnerable to Smilian objections” (page 88), referring to Vaclav Smil, a researcher who has criticized net-zero projections as unrealistic. Kolbert concedes that, while the positive innovations and changes she documents in the book are promising, they may not be adequate to draw down emissions fast enough. “To say that amazing work is being done to combat climate change and that almost no progress has been made is not a contradiction; it’s a simple statement of fact” (page 91).

In the remaining chapters, Kolbert explores this complexity more deeply. She writes about the challenges inherent in decarbonizing the power grid, dismantling the fossil fuel industry, and reimagining industrial and agricultural production. She catalogs the lack of political will in the U.S., countries not meeting timelines for carbon reduction pledges, and the failure of wealthier countries to adequately keep promises of financial support to developing nations. She documents the impacts of extreme heat on the human body and the dangers posed by positive feedback loops. And she outlines how extreme weather is damaging infrastructure and fueling climate migration.

Kolbert does not sugarcoat it. The hurdles we face seem insurmountable. At the same time, she reminds us, circling back to Thunberg, “You can’t just sit around waiting for hope to come … hope is something you have to earn” (page 147).

While perhaps not the message of certainty and solace that some might wish for in this time of ecological crises, Kolbert’s nuanced and visually compelling story of climate change offers readers a glimmer of possibility while also showing the very real obstacles we’re up against.

H is for Hope: Climate Change from A to Z

Author: Elizabeth Kolbert

Illustrator: Wesley Allbrook

Publisher: Ten Speed Press