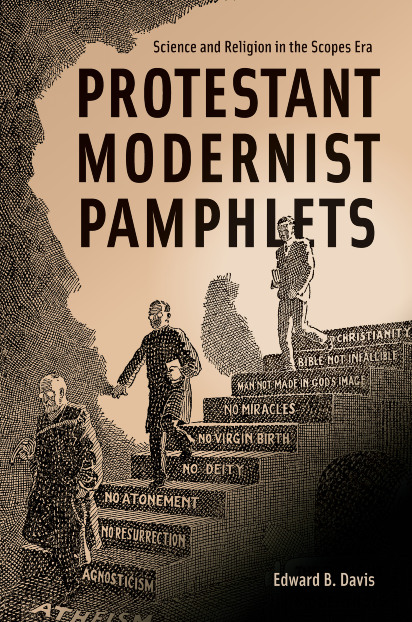

[Review] Protestant Modernist Pamphlets: Science and Religion in the Scopes Era

The author "presents what began as a reaction to the antievolutionist crusade of the 1920s, and in particular to William Jennings Bryan," our reviewer writes.

Protestant Modernist Pamphlets reprints 10 pamphlets published between 1922 and 1931 by the American Institute of Sacred Literature in its “Science and Religion” series, with annotations and a lengthy introductory essay by the historian of science Edward B. Davis. Thirty years ago, Davis edited a collection of the antievolution pamphlets of the creationist Harry Rimmer for Ronald L. Numbers’s Creationism in Twentieth-Century America series. Here, however, he presents what began as a reaction to the antievolutionist crusade of the 1920s, and in particular to William Jennings Bryan, whose invited column on “God and Evolution” appeared in The New York Times on February 26, 1922.

Was this the column that launched a million rebuttals? Scientists like Edwin Grant Conklin, a Princeton University zoologist, and modernist clergy like Harry Emerson Fosdick, a Baptist minister in New York City, were quick to respond in the pages of the Times, but the apparent growth of the antievolution crusade seemed to require a continuing response. The AISL — “a correspondence school for Protestant pastors administered by the University of Chicago Divinity School,” as Davis explains — stepped up to the plate, issuing a revised version of Conklin’s response and the original version of Fosdick’s response as the first two installments in the “Science and Religion” series.

Was this the column that launched a million rebuttals? Scientists like Edwin Grant Conklin, a Princeton University zoologist, and modernist clergy like Harry Emerson Fosdick, a Baptist minister in New York City, were quick to respond in the pages of the Times, but the apparent growth of the antievolution crusade seemed to require a continuing response. The AISL — “a correspondence school for Protestant pastors administered by the University of Chicago Divinity School,” as Davis explains — stepped up to the plate, issuing a revised version of Conklin’s response and the original version of Fosdick’s response as the first two installments in the “Science and Religion” series.

In a document entitled “Implication of the Scope [sic] Trial,” apparently written during the Scopes trial itself, the AISL complained that the trial showed “that religious prejudice is intolerant and incapable of fair play,” which Davis suggests alluded to the fact that the jury was not permitted to hear testimony from religious scientists and liberal theologians — the AISL’s crowd, essentially. (Reproducing the document in its entirety would have been nice.) “In any case,” Davis writes, “Bryan’s confrontational attitude toward evolution profoundly discouraged the kind of conversation that the AISL tried to facilitate” (page 78). And yet evolution was not front and center in the following installments.

Throughout the series, the authors were concerned to argue for the compatibility of science with faith, if not necessarily with the complete set of traditional religious beliefs that fundamentalists — but not only fundamentalists — were unwilling to revise or abandon in response to the challenges apparently posed by the deliverances of contemporary science. Notable contributors included the Nobel-Prize-winning physicist Robert A. Millikan and the Pulitzer-Prize-winning physicist Michael Pupin (who, as Davis acknowledges, was neither a Protestant nor a modernist), as well as the Harvard University geologist Kirtley F. Mather, who was prepared to testify at the Scopes trial.

A recurrent theme in Davis’s discussion is the influence of the conflict thesis — the idea that science and religion are intractably opposed and therefore have been in irreconcilable conflict through their history — on the AISL authors. Of Andrew Dickson White’s A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom (1892), which was particularly influential, Davis writes, “[T]he modernists and many others accepted its contents unquestioningly, embraced its attitude uncritically, and often mimicked his over-the-top rhetoric” (pages 96–97). As its title suggests, White’s book opposed “theology,” i.e., dogmatic religion, rather than religion per se; the AISL authors tended to agree.

So it is ironic that a handful of these modernist authors invoked what is in fact premodern philosophy. For a central example, Shailer Mathews, the dean of the University of Chicago’s Divinity School, argued in “How Science Helps Our Faith” (1922), “But if there is that within this rational and purposeful activity which in the course of evolution results in personal life, then there must be that within the activity itself which is at least as personal as we” (page 141, emphasis in original; Millikan and Mather offered similar claims in their pamphlets). But Mathews’s inference is intelligible only in light of ancient (and then medieval) views about the nature of causation.

Relying on his archival research, Davis describes the history of the AISL’s series in detail. Understandably, the AISL was sometimes lucky and sometimes unlucky in obtaining permission to reprint existing articles and recruiting contributors to prepare new pamphlets. Substantial funding was provided not only by eminent scientists but also by John D. Rockefeller Jr., the wealthiest man in the United States at the time, thanks to the cultivation of his minister by Shailer Mathews. Between 1922 and 1931, Rockefeller donated more than $24,200 to the AISL (about $440,000 in today’s money). Reactions to the pamphlets was mixed, as Davis shows through a series of entertaining quotations from the AISL’s archives.

By the time the series ended, owing partly to the waning of the antievolution crusades of the 1920s, about a million pamphlets had been distributed, in the primary hope of reaching “young people in churches, colleges, and universities.” For Davis, however, their enduring value is in illuminating “what leading scientists and modernist religious thinkers thought of the relationship between science and religion.” With the caveat that their presentations may have been simplified and perhaps even subdued by the need to address a general readership, Protestant Modernist Pamphlets makes a convincing case that he is correct.