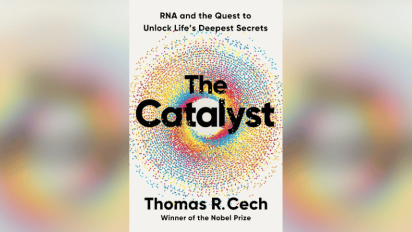

[Review] The Catalyst: RNA and the Quest to Unlock Life's Deepest Secrets

"Cech offers an intriguing tale, enhanced by vignettes of his personal interactions with many of the major players," our reviewer writes.

RNA has been playing second fiddle to DNA’s lead in the popular imagination ever since Watson and Crick deduced the double helical nature of our genes three quarters of a century ago. That view is changing, with RNA now understood to possess diverse catalytic abilities that DNA lacks, and thus to play a range of previously unsuspected roles in all living things. This shift reflects the work of Thomas Cech (who shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for 1989) as much as of any other single researcher. Cech was there at the beginning and remains active to this day. The Catalyst elucidates RNA science for non-scientists while illuminating both the process of discovery and the personalities of many of the researchers involved.

The book comprises two parts. The first (“The Search”) provides some needed background on molecular biology. It was once thought that RNA served primarily as intermediary between gene (i.e., DNA) and protein end product. Simple base pairing, either with DNA or other RNA molecules, was RNA’s specialty. Cech then presents his growing suspicion, radical at the time, that RNA had other tricks up its sleeve. The surprising discovery that the enormously long nuclear RNA transcripts found in higher organisms (eukaryotes) are extensively processed, or spliced, into much smaller messenger molecules before they can direct cytoplasmic protein synthesis is followed by the even greater shock that one of the molecules doing that splicing, in the case of Cech’s favorite critter at the time, Tetrahymena, is the RNA itself! For the preceding 60 years of research, every biochemical change — the making or breaking of molecular bonds — accomplished by a cell’s enzymatic machinery was, when studied in detail, shown to be performed by some protein. Many thousand such protein enzymes had been purified and characterized. Now, somehow, RNA could act similarly! (I can still recall my own surprise when reading Cech’s astonishing report 40-plus years ago.)

The book comprises two parts. The first (“The Search”) provides some needed background on molecular biology. It was once thought that RNA served primarily as intermediary between gene (i.e., DNA) and protein end product. Simple base pairing, either with DNA or other RNA molecules, was RNA’s specialty. Cech then presents his growing suspicion, radical at the time, that RNA had other tricks up its sleeve. The surprising discovery that the enormously long nuclear RNA transcripts found in higher organisms (eukaryotes) are extensively processed, or spliced, into much smaller messenger molecules before they can direct cytoplasmic protein synthesis is followed by the even greater shock that one of the molecules doing that splicing, in the case of Cech’s favorite critter at the time, Tetrahymena, is the RNA itself! For the preceding 60 years of research, every biochemical change — the making or breaking of molecular bonds — accomplished by a cell’s enzymatic machinery was, when studied in detail, shown to be performed by some protein. Many thousand such protein enzymes had been purified and characterized. Now, somehow, RNA could act similarly! (I can still recall my own surprise when reading Cech’s astonishing report 40-plus years ago.)

There follow informative chapters on the structure and workings of ribosomes, the enormous cellular complexes that make all new proteins. Once again, despite the presence of dozens of ribosomal proteins, it is a central RNA we now know that serves as catalyst. “The Search” concludes with fascinating speculation, backed up by current research, as to how RNA might explain the origin of life itself. If proteins need DNA to encode them, but DNA needs protein enzymes to replicate, how could life ever have begun? RNA on its own, it is now clear, is capable both of encoding information and of replication. Perhaps RNA is the key to this long-standing chicken-and-egg riddle, substituting for both DNA and protein in Earth’s first living things.

The second half of the book (“The Cure”) presents recent advances in medicine in which RNA plays a starring role. RNA turns out to encode the puzzling strings of repeated DNA (“telomeres”) found at the ends of all eukaryotic chromosomes; Cech, along with former students and collaborators, made key contributions to our understanding. Might longer telomeres be a secret to longevity, a ticket to unlicensed (i.e., cancerous) growth, or both? Stay tuned. RNA serves as the highly mutable genome of some nasty human viruses, in particular SARS-CoV-2, responsible for the Covid 19 pandemic. But RNA-based technology also underlies our most effective vaccines against that same virus, vaccines created many times faster than had ever been done before. Finally, RNA sequences aim the enzymatic machinery termed CRISPR at specific genes (of crop plants, mosquitoes, or humans) with unprecedented efficiency and precision, enabling genetic modifications that researchers hope will increase food production, ward off illness, and eventually cure serious congenital diseases.

The Catalyst is written in clear and compelling fashion, free of jargon and unnecessary details. It explains complicated science in appropriately simple terms aided by clever analogies: if the cumulative effect of diverse regulatory RNAs on gene expression is confusing, imagine instead what a snowstorm, a stalled truck, and the closing of the Brooklyn Bridge would do, individually and collectively, to Manhattan traffic. Cech offers an intriguing tale, enhanced by vignettes of his personal interactions with many of the major players. Outstanding women and international scientists, it’s worth noting, are prominently featured. In short, The Catalyst is a good read.

I would offer one quibble, and it is, ironically, with the use of the terms “catalyst” and “enzyme.” As Cech makes eminently clear in his scientific writings, and even in the glossary of this book, a true enzyme (like other, non-biological catalysts) accelerates a chemical reaction, RNA splicing for example, without itself being changed by that reaction. That wasn’t true in the case of the self-splicing of Tetrahymena RNA Cech reported in 1982; rather, a different RNA molecule, reported a year later by Cech’s Nobel co-laureate, Sidney Altman, first satisfied that criterion. Of course, as this book relates, many other bona fide RNA enzymes, “ribozymes,” have followed (including a processed form of the original Tetrahymena RNA, as Cech discovered a few years on). And while in the many medically significant examples presented later in the book, RNA plays key roles — as viral genome, as messenger RNA template for vaccines, or as a base-pairing guide for telomerase or for gene targeting — in none of these cases is the RNA itself catalytic. But then perhaps we should lighten up, and revert to more common parlance. As Cech writes, “RNA is already catalyzing a revolution in medicine” (page 125). With that, there can be no quibble.