The fossil record is one of the most common subjects about which creationists argue. They claim that evolution cannot possibly be true because the fossil record is riddled with gaps, that various life forms appear abruptly and without a trace of ancestry, and that there are no transitional or intermediate forms between the various fossilized organisms.

It is indeed true that the fossil record contains gaps and that forms often appear abruptly. It is not true, however, than ancestral and intermediate forms do not exist. There are many familiar examples of fossil series, such as that of the camel, horse, deer, tapir, rhinoceros, elephant, and hominid sequences, that demonstrate relatively gradual changes over time. In fact, the fossil evidence for the evolution of the camel, beginning with its small, four-toed ancestor, is so extensive and step-by-step that no company or organization in America will go to the expense of publishing all the data in one place.

The sequence of titanotheres is among the lesser known mammal series. These fossilized animals, dug out from the White River deposits of Colorado and adjacent states, begin in the Lower Eocene with an animal a little larger than a pig. As we move up the geologic column, we see this form evolve progressively into a larger animal with progressively larger horns. The record shows that these horns move forward from near the eyes to a position projecting out over the snout. The last of the line, in the lower Oligocene, has a head a meter long with horns of over thirty centimeters. This series represents over twenty million years of evolutionary change.

Besides mammals, there are marine organisms with long fossil histories, such as the sea urchin, snail, and trilobite. Dr. Niles Eldredge of the American Museum of Natural History has devoted considerable study to these, in particular to the evolution of the trilobites. In his book, The Monkey Business, he goes

into some detail on the various evolutionary stages leading to a particular suborder of trilobites, the phacopids. He further points out, "Trilobites are as diverse and prolific as the mammals, and examples of evolutionary change linking up two fundamental subdivisions of the 'Class Trilobita' ... are as compelling examples of evolution as any I know of" (p. 118).

All the above-mentioned sequences are quite complete, though their pattern is not a linear progression as most persons imagine it should be. The fossil evidence rather shows a radiating or "tree of life" pattern, often involving many offshoots, regressions, and uneven developments. This is what should be expected. Too even and progressive a development might imply design—and hence creation.

Creationists in debate understandably refrain from mentioning such series as these. They prefer to concentrate on animals further back in the fossil record for which the evidence is less complete and where "abrupt appearances" are more common. Dinosaurs and other Mesozoic reptiles are a preferred target. Duane Gish of the Institute for Creation Research is fond of running through a series of slides of these animals during his debates and claiming that each is a sudden appearance in the record and is unrelated to any other animal.

Dr. Gish includes one slide of a Triceratops dinosaur. When I first saw him present this, I was amazed that Dr. Gish could be unaware of the well-known ancestry of this animal. But, in debate after debate, he persisted in claiming that Triceratops had no ancestors, that no similar dinosaur existed with anything less than its full set of three horns. On page twenty-one of his book, Dinosaurs, Those Terrible Lizards, he committed himself in print.

Nowhere do we find in-between forms with spikes starting out as little spikes which gradually got bigger and bigger and finally ending up as a Triceratops dinosaur. The first time you see a dinosaur with armor plate on its head and with three spikes, he is a full-fledged Triceratops, with a huge armor plate and with three big spikes. This is strong evidence for creation!

Every sentence of this is false. First, there definitely are in-between forms in the fossil record which have lesser and smaller "spikes" (horns); Dr. Gish denies that these exist. Second, Triceratops is not the only dinosaur with "armor plate [bony frill] on its head and with three spikes." He ignores Pentaceratops and Torosaurus, among others, which also fit this description.

To make the point clearer, however, it will be useful to review the evidence for the evolution of the ceratopsians—or horned dinosaurs—by covering each link of the evolutionary chain in some detail and by providing illustrations.

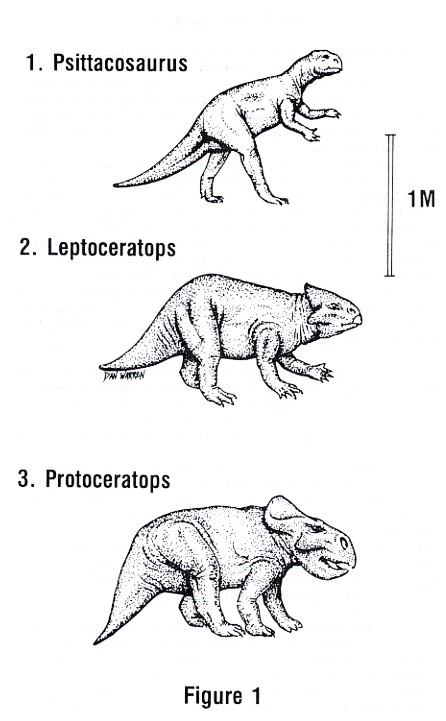

Psittacosaurus (sit-a-ko-SAWR-us), or "parrot lizard," begins our story. This

animal lived some 118 million years ago in the Lower Cretaceous period. Its

fossils are found in the Ondai Sair Formation of Mongolia and in the Lower

Cretaceous rocks of Kansu and Shantung in China.

It is classified as a ceratopsian because of the features it shares in common with the later members of the ceratopsian "family tree," namely the sharp downturned upper jaw which resembles the beak of a parrot and the beginnings of a bony frill at the back of the skull. Psittacosaurus could walk on its two hind legs or on all fours, but the two-legged posture seems to have been its most common method of locomotion. It was about a meter and a half long.

The only major caveat in the proper placement of this dinosaur is that all species so far found, such as Psittacosaurus mongoliensis (pictured at the top of Figure 1, page 4), could not have been the direct ancestors of the later ceratopsians. This is because the teeth in the front of the upper jaw found in the later Protoceratops are already absent in the extant fossils of Psittacosaurus. Nonetheless, it was an animal from this same genus that was the direct ancestor, and the species we do have indicate what the missing example must have been like. (As Niles Eldredge argues on page 125 of The Monkey Business, it isn't a major problem for evolution or for classification of species if one lacks the ancestor of a given form. Often later cousins will provide us with most of the information we need. Furthermore, because very few animals are ever fossilized, it should come as no surprise that pieces in the story are often missing.)

Leptoceratops (lept-o-SER-at-ops) allows us to discuss the next step. About 100 million years ago, the family called the Protoceratopsids appeared on the scene. This was in the Upper Cretaceous. Leptoceratops was a North American genus that was actually the last representative of this family. However, it has been determined to have been a slightly modified survivor of the ancestral group that later developed into Protoceratops.

At least six examples of Leptoceratops have been found in the Upper Edmonton Formation of the Red Deer River in Alberta, Canada. Leptoceratops gracilis is the species pictured in the center of Figure 1. The skeleton and skull show a very primitive structure, but demonstrate a later change in that two teeth are absent. The bony frill over the neck, which is a feature of the later ceratopsians, is only slightly developed. The feet and hands still show the claws common to Psittacosaurus, but Leptoceratops probably walked less often in the twolegged posture. In size it falls about midway between Psittacosaurus (top, Figure 1) and Protoceratops (bottom, Figure 1).

Protoceratops (Prot-o-SER-at-ops) was a direct descendant of the ancestral line that produced Leptoceratops. Protoceratops was about two meters long, was more heavily built than its predecessors, and had claws that showed a change toward the small hooves common to the later ceratopsians. Its frill was fully developed, and this increase in size was directly related to the larger neck and jaw muscles which were, themselves, related to the powerful shearing teeth that allowed the animal to consume tougher plant material.

As in the previous stages in the evolution of the ceratopsians, Protoceratops had hind legs longer than its forelegs. It was able to stand on the hind legs while digging in the ground with the forelegs. But, aside from that, Protoceratops walked fully on all fours.

Protoceratops andrewsi is the only species known, but there are a large number of specimens of differing growth stages covering everything from hatchling to adult. Over a hundred skeletons showing these stages were found in 1924. Nests of eggs were also discovered. All the finds have come from the Djadochta Formation of Shabarakh Usu in the Gobi Desert of Mongolia and from the Ulan Tsonch Formation in Kansu, China.

The presence of Leptoceratops in North America, as well as the presence of close

cousins and identical genera of other types of dinosaurs on both continents,

indicates that passage was relatively easy between the continents at the time

these dinosaurs were evolving. Therefore, it is easy to see how Protoceratops is

the direct ancestor for the next stage, Monoclonius.

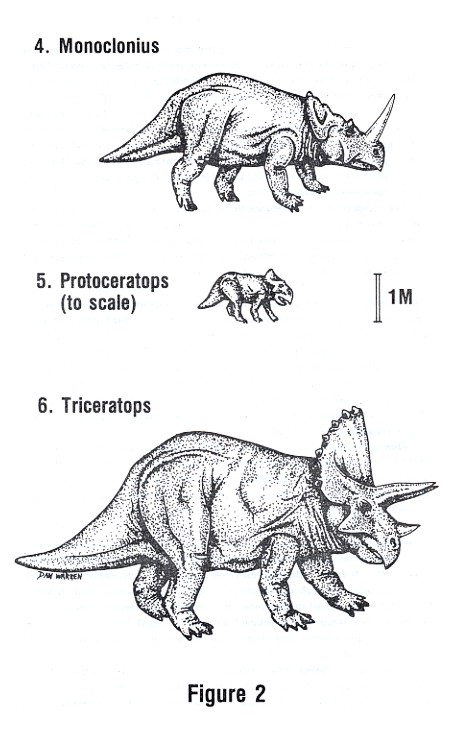

Monoclonius (mon-o-KLON-e-us), like all the later examples of the Ceratopsid

family, evolved on the North American continent during the Upper Cretacious

period. There are a number of fossil species extant, including Monoclonius

nasicornus (top, Figure 2), Monoclonius crassus, the first example found, and

Brachyceratops montanensis, which, though sometimes thought to be of a directly

ancestral genera, is more often held to be a juvenile form of still another

Monoclonius species. All of these were found in formations in Montana except for

Monoclonius nasicornus which came from the Oldman Formation in the Red Deer

River in Alberta, Canada.

Monoclonius first appeared about ninety million years ago. It reached a length

of approximately six meters and had a large horn on its nose and incipient brow

horns over the eyes. The frill featured a strongly crenulated margin of dermal

bones on its edges, though not as developed as a similar structure in the later

Triceratops.

Triceratops (try-SER-a-tops), pictured at the bottom of Figure 2, was the largest of the ceratopsians and the end of the direct line from Protoceratops through Monoclonius. It evolved about seventy-five million years ago and lived to the end of the Cretaceous, which ended about sixty-three million years ago. It was so hardy that it was one of the last dinosaurs to survive. It reached a length of nine meters and had three fully developed horns on its head. The brow horns were sometimes nearly a meter long. The margin of the frill featured a row of dermal bones, somewhat limpet-shaped.

Triceratops horridus and Triceratops prorsus are two well-established species. Fossils have been found in the Lance Formation of Wyoming, in Colorado and Montana, and in the Canadian provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan.

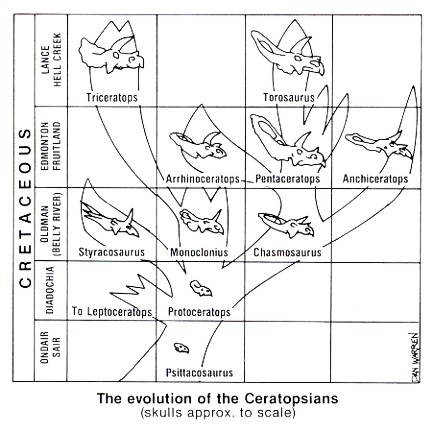

The ceratopsian "family tree" shows a number of separate lines of development. Besides the sequence just outlined, there is another major sequence going from Protoceratops to Chasmosaurus to Pentaceratops and ending with Torosaurus. This is the long-crested line, shown on the right side of Figure 3. The short-crested line, ending with Triceratops, is on the left side. There were many offshoots in the evolution of these dinosaurs too involved to be shown in the diagram.

Two of particular interest that are not shown are Bagaceratops and Montanoceratops. Bagaceratops was a strange mixture of advanced and primitive characteristics among the Protoceratopsids. For example, although it had a clearly formed horn core above its nose, its frill was only slightly developed. It probably filled a different ecological niche from its larger relative, Protoceratops. Its existence demonstrates the variety of transitional forms possible.

Montanoceratops is another example of a transition. It is so transitional, in fact, that paleontologists cannot always agree on where to place it. Some say that it is an advanced Protoceratopsid while others declare it to be a very primitive member of the family Ceratopsidae.

The dilemma is caused by the fact that, although it still had claws rather than hooves and was only three meters long, a nasal horn was developed, it had longer forelegs, and it had the more robust body proportions of the later and larger ceratopsians. As its name implies, this dinosaur was found in Montana.

These sorts of classification problems are exactly what would be predicted in the light of evolution, but they don't make sense if creationism is true. Difficulty in classification means a lack of distinct separateness between forms. It means one form sometimes almost bleeds into another. Creationism, however, requires very clear distinctions and wide, unbreachable gaps. In the case of the ceratopsians, the evidence overwhelmingly favors evolution.

It should now be clear that the facts from the fossil record utterly destroy Dr. Gish's claim that Triceratops appears abruptly in the fossil record without a trace of any ancestors. It was certainly clear to me when I presented a small portion of this data to him in debate on February 2, 1982, at the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada. But his response was interesting. He declared that, since all the fossils from Protoceratops through Triceratops were found in the Upper (or Late) Cretaceous strata, they couldn't be an evolutionary sequence. To be an evolutionary sequence, he claimed, these examples would have to stretch back to the Jurassic or Late Triassic.

First of all, Dr. Gish ignores the fact that Psittacosaurus fossils were found in the Lower (or Early) Cretaceous. And second, he ignores the fact that the evolution just from Protoceratops to Triceratops spanned a period of over twenty-five million years. (Add Psittacosaurus and it expands to nearly forty-five million years). That is plenty of time for evolution to take place. Furthermore, it is important to note that the fossils all appear in the correct order; that is, you don't find Triceratops below Protoceratops, you don't find Protoceratops up above Monoclonius. The fossils appear in proper sequence and show developmental change. They progressively grow in size, number of horns, size of frill, and strength of jaws. Also certain features remain constant throughout the sequence-for example, the parrot-like beak and the hind legs always being somewhat longer than the forelegs. There are many other features that could be catalogued in this way, too, and have been in the standard scientific literature.

Dr. Gish gave no further response in that debate. However, he was once more confronted with this data in a debate on March 21, 1982, in Tampa, Florida. In this debate with Dr. Kenneth Miller, Gish replied:

Now let me reply to, well, let's have the next slide, please, quickly. There's a Triceratops. There he is. And supposedly he came from a Protoceratops. That Protoceratops had no horns. He had a horny sheath, something like that. And supposedly it evolved into this creature, with that heavy armor and so forth. No intermediates are found.

Although he was right that Protoceratops had no horns, he was wrong that there are no intermediates. He had already been shown Monoclonius, complete with its large nasal horn and two incipient horns over the eyes-which are located in the same place as the large horns in Triceratops. It was necessary to repeat this point and to note that the evidence for Monoclonius involves, in at least one case, a complete skeleton—it has not been the product of reconstruction.

Dr. Gish gave no answer and seems to have none, and this puts him at the horns of a dilemma. There are only three ways he can go if he wishes to preserve creationism. He can accept the evolution of the ceratopsians but deny that any other evolution took place. He can claim that all these dinosaurs were separately created (which is why they all look so different from each other). Or he can claim that they are all the same basic created "kind" (which is why they all look so much alike).

The first choice isn't acceptable because it admits to evolution and leaves the door open for me to go after another of his dinosaur slides in my next article (such as Stegosaurus, which also had ancestors he claims did not exist). The second choice will not do because it implies a creator who experiments with first this and then that until he comes up with something he likes. Furthermore, Noah has to load all these experiments onto the ark. The third choice is his best escape and the one that creationist Luther Sunderland chose when I presented him with the same dilemma in a CBC radio debate, taped on May 7, 1982, in Toronto, Canada.

On that program, Sunderland argued that growth in size of body and horns is not uncommon in animals and thus the development of the various ceratopsians is perfectly consistent with the notion of variation only within the originally created "kinds." After the taping, we discussed the evolution of the horse. With this series, too, Sunderland argued that the changes in size and number of rib bones could be accounted for as mere variation within a basic kind. He argued that the present breeding of midget horses shows that horses can be bred small, and he indicated that it might therefore be possible to recreate the stages found in the horse series of the fossil record (excluding Eophippus, which he held to be a different "kind" entirely).

This line of argument is further developed in Biology: A Search for Order in Complexity by John N. Moore and Harold S. Slusher (pp. 418-420). There it is claimed that fossil horses could simply be small breeds, horses that didn't get proper nutrition, or even sterile hybrids that left no ancestors. The problem with this whole manner of discounting the evidence is that it ignores the large number of individual specimens, their patterned geographical spread showing migration and evolution together, and their appearance in the proper order in the geologic column. Creationists, in order to use this argument, have to believe that all the stages of horse evolution are actually exceptional cases of modern horses in an abnormal condition. Not one fossilized example can be anything other than this.

Such is the length to which creationists must go in order to answer the clear fossil finds of not only horses but ceratopsians and most other evolutionary series.

Moore and Slusher also accept Darwin's finches as examples of simple variation (pp. 463-466). However, since finches represent transitional changes at the species level and the ceratopsians represent changes at the genera and family levels, when creationists accept both, they define "created kind" in such a broad manner that they can accommodate a great amount of evolution in the name of creation. In their eyes, then, changes anywhere within a family can be dubbed "micro-evolution" and made part of the creation model.

But Niles Eldredge has discovered that creationists will accept even more evolution than this in some fossil sequences. In The Monkey Business, Eldredge notes that the thousands of species of fossil trilobites which have been classified into a number of families, superfamilies, and orders are passed off by creationists with the argument that they are all just trilobites and so it doesn't matter (p. 118). Eldredge writes:

But, apparently to creationists, if you've seen one trilobite you've seen them all, and all changes paleontologists have documented in this important group of fossils are just "variation within a basic kind." . . . Airily dismissing 350 million years of trilobite evolution as "variation within a basic kind" is actually admitting that evolution, substantial evolution, has occurred.

This brings us back to Dr. Gish and the ceratopsians. In his book, Evolution: The Fossils Say No!, he has this to say about "kinds":

Among the vertebrates, the fishes, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals are obviously different basic kinds.

Among the reptiles the turtles, crocodiles, dinosaurs, pterosaurs (flying reptiles), and ichthyosaurs (aquatic reptiles) would be placed in different kinds. Each one of these major groups of reptiles could be further subdivided into the basic kinds within each. (p. 34)

The way he uses the term kind here, one would think that there are different levels or "kinds of kinds." For example, reptiles are a kind, and within that kind is the dinosaur kind, and, I would assume, within that is the ceratopsian kind. Now where is the common ancestry and where is creation? Clearly, Dr. Gish has a loose enough definition of kind that, if people keep throwing the ceratopsians at him in debate, he can eventually fall back on the argument that they are all the same kind.

It is no problem for evolution if creationists do this. It is rather a problem for creation. It means that creationists are retreating in the face of overwhelming evidence. It means that they are admitting to more and more evolution. It means that they are gradually giving their case away.

This is why I am sometimes surprised when Dr. Gish bases so much of his debate arguments on the fossil record.

This record isn't as helpful to him as he may have thought it was. We recently have seen more and more creationists admitting that they do see evidence for transitional forms, that they do find intermediate types, and that fossil sequences without major gaps do exist. The transitional forms that creationists have tried to tell us "are nowhere to be found" are actually quite plentiful. This is why creationists have modified their model. Instead of having a creation model that predicts gaps, they now have one that predicts transitional forms and complete lineages.

It seems that creationists have a very flexible position.