To fully understand how to interpret an ancestry test, to make informed decisions about GMOS, or even to grasp the etiology of cancer, one first must understand the underlying evolutionary theory. For example, ancestry tests are based on genetic drift and the paths of the Out of Africa dispersals of early members of our species 100,000 years ago. NCSE works to break down barriers between scientists and nonscientists by creating evolution content that is both accessible and relevant to people’s lives. By helping people to see links between evolutionary theory and their own health, we are enabling them to overcome their hesitancy about evolution and creating opportunities for their deeper engagement with the science.

For the past year, NCSE has been exploring ways to partner with museums and other informal science learning centers to help them provide activities that make science more accessible to broader audiences. Research shows that people rely on the news, social media, and informal science outlets for science-related information. While informal science venues like museums and science centers are the most trusted, they also are some of the least commonly accessed, often because of cost and distance.2 Museums are therefore a crucial way to communicate accurate information to the broader public, if we can remove some of the barriers associated with accessibility.

Let the investigation begin

Two of NCSE’s current Graduate Student Fellows, Keighley Reisenauer and Abigail Howell, and I, a former Graduate Student Fellow, started a research project to better understand what genetic information is available to communities across the country and whether — and if so, how — it provides necessary tools for individuals to make educated health choices. Our project seeks to assess both access to genetics exhibits in museums and the effectiveness of these museums in helping people make informed decisions.

“There are real-world consequences for people not understanding genetics — medical consequences of genetic health testing … misinterpreting/misusing their ancestry results, and the impacts this has on social justice/equity measures, or having a policy against GMOs without understanding what they are,” explains Howell about the importance of the project. Ultimately, the fellows hope to provide reliable and accessible information to aid in evidence-based decisions, but also to find the most effective way to do so. This will be accomplished through the development of a mobile genetics exhibit that will not only discuss fundamental genetics concepts (e.g., DNA, evolution, etc.), but also present genetics topics relevant to our everyday lives such as GMOs and genetic testing.

What our research is showing

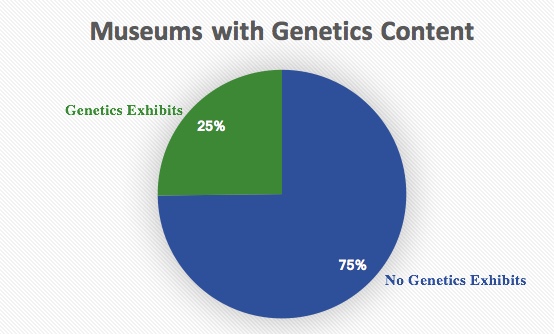

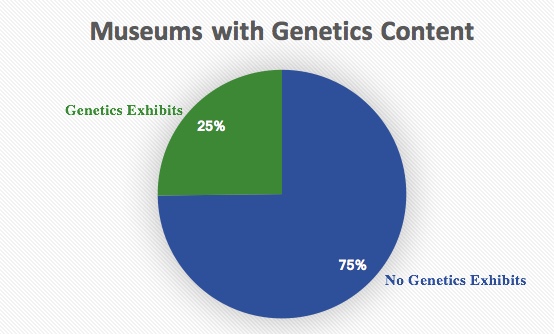

As part of our research into the topic, we compiled a list of informal science education spaces across the United States that could potentially host a genetics exhibit. The list included science centers, natural history museums, children’s museums, and state museums. Of the 270 museums analyzed, 202 museums lacked an exhibit that had any genetics-centered information. There were also 6 states (Mississippi, Rhode Island, Vermont, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming) that lacked genetics exhibits altogether, forming “genetics information deserts.”

We also found that not a single one of the children’s museums in our study had genetics-based information, though some did have a health-focused (doctor’s office or exercise) component. A lack of introduction to genetics at a younger age, may in part, explain an overall mistrust of genetic-based information seen in adults.

In addition, to better understand the learning goals and components of genetics exhibits, we reached out to curators and exhibit directors of the museums to conduct formal interviews. Among the museums that do have genetics exhibits (permanent or traveling), 13 have participated in the interviews so far. The wealth of knowledge learned from these individuals has been truly incredible, and we are grateful for their willingness to participate.

When I asked the fellows about the project and what they were learning, they couldn’t say enough good things. “I loved how Judy Diamond from the University of Nebraska Museum talked about their impact on how people understood evolution — 'you couldn't change their baseline identity, but you could subtly change how they thought about genetics and evolution' — and how that’s still a big impact,” Howell said.

Howell continued: “I think the most surprising thing is the content presented is very specific to each museum, based on what it has in its collections, what types of research the people who work there are doing, and what the public wants.” While each museum had unique approaches to the content within the exhibit, there were some underlying themes that presented themselves. There was an emphasis on making the material relevant, a need for interactive components, and the importance of including the research of local scientists. Using these unique perspectives and shared concepts, we hope to develop a traveling genetics exhibit that provides educational information by presenting engaging activities and thought-provoking displays.

Traveling exhibit

The traveling exhibit will take the information learned in the research study and identify the important genetic concepts that should be included. We are currently designing an exhibit to travel to libraries across the nation. Why libraries? Because they are open and accessible to the public, removing barriers and creating equal access.

“We found studies that showed how there is widespread misunderstanding of genetics concepts and how they are used in areas like policy, public health, and culture. By creating an exhibit that can travel to multiple communities, we aim to reduce this knowledge gap and increase educated action,” Reisenauer explains. “I hope that people can connect with the content and go a little further than just learning. I hope it can spark conversation and even, perhaps, lower the barriers to understanding science.”

Both Reisenauer and Howell are excited to see this effort unfold and can’t wait to visit the exhibit when it comes to their hometowns. The mobile genetics exhibit is set to start its tour in the fall of 2020.

1. Chapman, R. et al. New literacy challenge for the twenty-first century: genetic knowledge is poor even among well educated. J. Community Genet. 10, 73–84 (2019).

2. How Americans Get Science News and Information. Pew Research Center’s Journalism Project https://www.journalism.org/2017/09/20/science-news-and-information-today/ (2017).