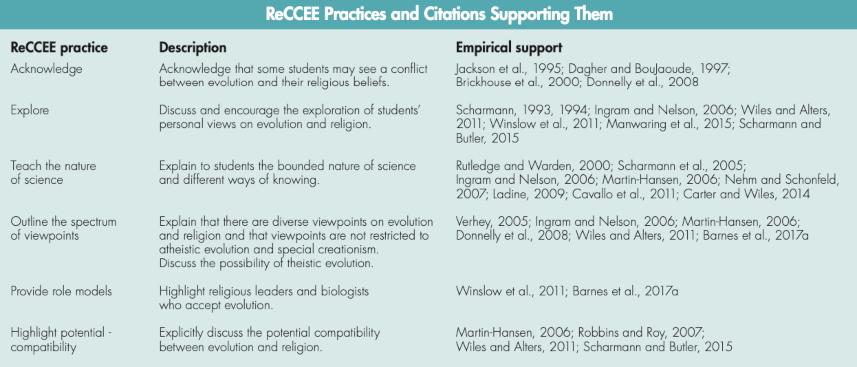

The research that led Barnes and Brownell toward the Religious Cultural Competence in Evolution Education framework involved conducting a series of studies with professors and students at public higher education institutions. They interviewed professors who were mostly secular about how they were teaching evolution and how they were addressing the perceived conflict between evolution and religion. “The instructors at secular institutions were mostly completely avoiding the topic,” Barnes said. “A small subset of those instructors were being actively hostile to religion. They weren’t really thinking about how their students’ religious backgrounds might be influencing how they were receiving their instruction.” The two then interviewed religious students from these professors’ classrooms. “Students were already coming in with this misconception that their religion had to be in conflict with evolution,” Barnes said. “Instructors not ad- dressing that only allowed that misconception to remain.”

Barnes has heard the refrain that it’s not a professor’s job to convince her students to accept evolution but rather simply to teach the concepts. She counters by saying that if an instructor doesn’t address what Barnes described as the single most predictive factor — namely religiosity — for rejection of evolution, then that is an oversight. “Instructors say it’s not my job to teach students to accept evolution,” Barnes said. “It’s so interesting that they say that about evolution. Because I don’t think we’d say that about other topics, like photosynthesis. If I were teaching photosynthesis and the whole class got an A on the test but 30 percent of students left the class thinking photosynthesis wasn’t real, as they do evolution, for me personally I wouldn’t see myself as a successful instructor.” Barnes added that helping students grasp the nature of science is critical if they are to develop greater acceptance of evolution. For instance, distinguishing be- tween methodological and philosophical naturalism in science and describing evolution more accurately as agnostic rather than atheistic improves religious students’ comfort learning and accepting evolution. As it stands now, Barnes and Brownell’s research shows that almost half of college biology students enter their classes thinking one has to be an atheist to accept evolution.

Barnes and Brownell are currently doing additional re- search on the Religious Cultural Competence in Evolution Education framework as part of a National Science Foundation grant. They’re attempting to determine the role the framework plays in improving acceptance of evolution by students who are religious. “What we’re seeing so far is that when instructors bring forth examples of religious scientists who accept evolution, students are more accepting of evolution by the end of the class. Conversely, if instructors are more negative about religion, we see lower acceptance of evolution at the end of instruction.” Such negativity, Barnes added, does not have to be overt. She and Brownell observed instructors who students rated as more negative about religion than other instructors. The forms of negativity about religion were not explicit. In one instance, a professor projected a comic that poked fun at a theistic version of evolution at the beginning of class. According to their analysis, subtle negativity such as this can lead to lower evolution acceptance among students.

Barnes and Brownell are currently doing additional re- search on the Religious Cultural Competence in Evolution Education framework as part of a National Science Foundation grant. They’re attempting to determine the role the framework plays in improving acceptance of evolution by students who are religious. “What we’re seeing so far is that when instructors bring forth examples of religious scientists who accept evolution, students are more accepting of evolution by the end of the class. Conversely, if instructors are more negative about religion, we see lower acceptance of evolution at the end of instruction.” Such negativity, Barnes added, does not have to be overt. She and Brownell observed instructors who students rated as more negative about religion than other instructors. The forms of negativity about religion were not explicit. In one instance, a professor projected a comic that poked fun at a theistic version of evolution at the beginning of class. According to their analysis, subtle negativity such as this can lead to lower evolution acceptance among students.

Are there implications in Barnes and Brownell’s research for K–12 education?

Barnes and Brownell are admittedly not K–12 education experts and their work focuses on college-level evolution education, Barnes noted. However, she observed that most public school biology teachers take college-level biology and are likely influenced by the biology instruction they receive in college. If college instructors are not culturally competent when teaching pre-service teachers, this could lead to those teachers being ineffective themselves. For instance, religious teachers may avoid teaching evolution due to unresolved personal conflict or secular teachers may themselves teach evolution in a way that is not culturally competent. “College instructors are the ones modeling evolution instruction for pre-service K–12 teachers. It’s all connected,” she said.

Barnes noted there is no shortage these days of science communication that involves cultural dissonance between groups. She has decided to turn her research lens toward climate change and students’ and professors’ political identities. “Here at Middle Tennessee State University, for instance, the majority of my students are politically conservative. So how are instructors, who are mostly politically liberal, taking this into account when they’re teaching about climate change?” Her hope, as with evolution education, is to figure out ways to reduce perceived conflict between political identity and acceptance of climate change, with the aim of creating more inclusive climate change education for students from different political leanings while also increasing those students’ comfort with accepting climate change themselves.

This version might differ slightly from the print publication.

Barnes and Brownell are currently doing additional re- search on the Religious Cultural Competence in Evolution Education framework as part of a National Science Foundation grant. They’re attempting to determine the role the framework plays in improving acceptance of evolution by students who are religious. “What we’re seeing so far is that when instructors bring forth examples of religious scientists who accept evolution, students are more accepting of evolution by the end of the class. Conversely, if instructors are more negative about religion, we see lower acceptance of evolution at the end of instruction.” Such negativity, Barnes added, does not have to be overt. She and Brownell observed instructors who students rated as more negative about religion than other instructors. The forms of negativity about religion were not explicit. In one instance, a professor projected a comic that poked fun at a theistic version of evolution at the beginning of class. According to their analysis, subtle negativity such as this can lead to lower evolution acceptance among students.

Barnes and Brownell are currently doing additional re- search on the Religious Cultural Competence in Evolution Education framework as part of a National Science Foundation grant. They’re attempting to determine the role the framework plays in improving acceptance of evolution by students who are religious. “What we’re seeing so far is that when instructors bring forth examples of religious scientists who accept evolution, students are more accepting of evolution by the end of the class. Conversely, if instructors are more negative about religion, we see lower acceptance of evolution at the end of instruction.” Such negativity, Barnes added, does not have to be overt. She and Brownell observed instructors who students rated as more negative about religion than other instructors. The forms of negativity about religion were not explicit. In one instance, a professor projected a comic that poked fun at a theistic version of evolution at the beginning of class. According to their analysis, subtle negativity such as this can lead to lower evolution acceptance among students.