[Review] Science v. Story: Narrative Strategies for Science Communicators

"Bloomfield uses her narrative web to analyze stories of climate change, evolution, vaccines, and COVID-19 ... But her focus on these controversies undercuts the book’s goal," our reviewer writes.

Science v. Story has an unfortunate title. It reinforces the misconception that “science” means “real” and “story” means “made up.” But the title of the last chapter, “Science and story” (emphasis in original) better describes what Emma Bloomfield has in mind: improving communication about science using storytelling.

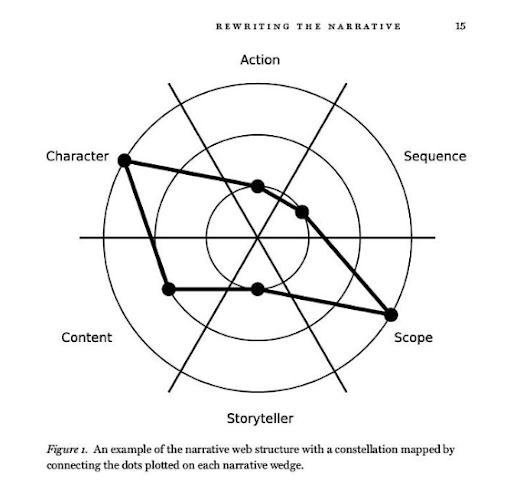

The invention that Bloomfield hopes will improve storytelling is the “narrative web.” Imagine a circle sliced into six pieces. Each piece represents part of a story: character, action, sequence, scope, storyteller, and content.

The invention that Bloomfield hopes will improve storytelling is the “narrative web.” Imagine a circle sliced into six pieces. Each piece represents part of a story: character, action, sequence, scope, storyteller, and content.

Now imagine the outer circle has two smaller circles nested within it, like a dartboard.

Each part gets one dot on one of those three circles. If part of the story is concrete and specific, a dot goes on the ring closest to the center. But if that part is abstract and general, the dot goes on the ring closest to the edge. If it’s in between—you guessed it—middle ring. Those six dots form a “constellation” that characterizes a story. (See fig. 1, below.)

It’s a complicated way to show “low, medium, high” for six aspects of a story. Moreover, Bloomfield often calls the levels the “micro-ring,” “meso-ring,” and “macro-ring”; the academic Greek doesn’t make picturing constellations from her descriptions any easier.

The narrative web is also a little non-intuitive to use. At first, Bloomfield says the three levels represent the range from “specific” to “abstract” for all story parts, but not all six work that way. For example, the “storyteller” part is rated not by specificity, but by the audience’s trust in the storyteller.

The subtitle, “Narrative Strategies for Science Communicators,” suggests this “how-to” book is for science communicators, but the narrative web tool and the writing style doesn’t seem well-suited for journalists, museum staff, or public information officers crafting stories about science. It seems better suited for academics analyzing stories about science.

Narrative webs’ use in analysis is obvious, but it’s not so clear how to use them to create effective stories. What constellation does a compelling story create on the narrative web? One might think that a good storyteller would cluster the points in the middle, like a sharpshooter. The saying goes, “The death of one is a tragedy” (specific, inner ring, strong story); “the death of many is a statistic” (abstract, outer ring, a mere fact). But Bloomfield says the inner rings are not always better. She encourages experimenting with bigger, more abstract concepts, pushing some dots closer to the edge of the web.

Bloomfield uses her narrative web to analyze stories of climate change, evolution, vaccines, and COVID-19. Her coverage of them is thorough, although skewed to the US. But her focus on these controversies undercuts the book’s goal.

Someone reading this book probably wants to learn how to use stories to convince people. But the Scopes trial is nearing its centenary, climate change and vaccination fights have gone on for decades, and rhetoric attacking the science relevant to COVID-19 seems to be becoming less rooted in science, not more. Science has not lacked good storytellers all that time, so there must be other reasons why these controversies persist.

Bloomfield explores those reasons—she is thorough—but it would have made her book more compelling to compare cases where opinion remains stubbornly stuck to cases where communication resulted in wins for science. For example: rockets went from being seen as weapons to vehicles for space exploration; Rachel Carlson’s Silent Spring convinced people pesticides were risky; people almost entirely stopped smoking in public spaces; legislation was passed that stopped acid rain and shrunk the ozone hole.

In all these cases, there were rival narratives like those deployed in opposition to climate change, evolution, and vaccination. Corporations foretold economic disaster if pesticides were regulated, as they did again with regard to fossil fuels. Smokers extolled the virtues of personal choice, much like anti-vaccine advocates. Without comparisons, it’s hard to know why some stories work but others stall.

If the narrative web is a general tool, what does the constellation for Science v. Story look like?

The dots for character, action, and sequence might rest in the middle ring: the book describes specific examples, but usually to illustrate bigger trends.

The scope dot goes on the outer ring, because Bloomfield aspires to show principles that apply to any story.

The storyteller dot sits firmly in the trusted innermost circle, because Bloomfield’s is a trusted narrator whose scholarship and thoughtfulness is unquestioned.

Finally, the content dot for relevance might sit in the middle ring, because it seems unlikely that all science communicators will find all the book’s material equally helpful throughout.