Over at Buzzfeed, Matt Stopera has an interesting post originating from the recent Bill Nye/Ken Ham debate. He asked self-identified creationists at this debate to write a question to “the other side,” and have their picture taken while holding their question.

It’s very interesting seeing the real faces of creationists and their real questions about science. Spelling and grammar in these off-the-cuff questions were challenges, but we expect that has more to do with the ubiquitously abysmal condition of American literacy, rather than a deficiency specific to creationist thought.

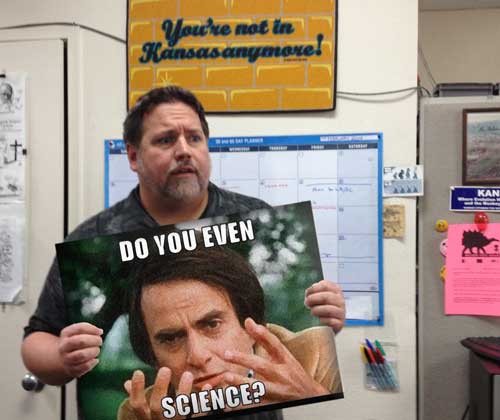

Here's my take:

Phil Plait offers responses to the Buzzfeed questions at his Bad Astronomy blog, but let me address a few of the more interesting questions here:

If evolution is a theory (like creationism, or the Bible) why then is evolution taught as a fact?

Because science by definition is a ‘theory’—not testable, observable, nor repeatable' why do you object to creationism or intelligent design being taught in school?

It’s unsurprising that two of Buzzfeed’s creationists asked questions about the word “theory.” At NCSE, we encounter misunderstandings of “theory” daily. People mistake the common usage of the word theory, meaning “guess,” with the scientific usage of the word theory, meaning a well-supported, broad explanation of natural phenomena. Same word, two different contexts.

The word “fact” in the first question presupposes that the theory of evolution will somehow have “graduated” from being a lowly theory to being an exalted fact. The truth is, it’s the other way around—facts first, theory second. Experiments help scientists determine facts, and from many such experiments, the outlines of a theory may emerge. On his famous voyage, Darwin observed a number of facts, such as the wide varieties of Galápagos finches; upon his return, he developed the theory of evolution to explain the origin of such facts.

The second question is unique in that it defines theory as “not testable, observable, nor repeatable.” This really could not be more wrong. Testing, observing, and repeating are all vital parts of assembling the evidence supporting theories; moreover, we can use theories to make predictions about things we don’t yet know, and such predictions are highly testable and repeatable. This level of misunderstanding about the word “theory” is baffling. One good source to help clear up confusion about the usage of “theory” is the Understanding Science website.

The question then goes on to ask, “Why do you object to creationism or intelligent design being taught in school?” Legally, there are very good reasons not to teach creationism and “intelligent design” in schools. Creationism and “intelligent design” are religious rather than scientific positions, so privileging any one religion over all others is a serious violation of the neutrality mandated by the Constitution. People of faith who value the freedom to worship in their own way can easily understand the danger of having the government “pick a winner” among the free market of faiths. Pedagogically, there are also good reasons not to teach creationism and “intelligent design” in schools; it is hard enough for students struggling to learn science, without needlessly confusing them with unsupported complaints about evolution originating outside of science.

How do you explain a sunset if their [sic] is no God?

How can you look at the world and not believe someone created/thought of it? It’s amazing!!!

Two creationists asked these similar questions, appealing to the beauty of nature as evidence against evolution. We see similar questions about Grand Canyon; surely, some visitors remark, a place as amazing as Grand Canyon could not have formed by random undirected processes? Surely a sunset requires something beyond science, right?

Here’s where scientists often miss the point; one could address the sunset question with a technical answer talking about light scattering and the electromagnetic spectrum, but non-scientists are not going to listen. There is a straightforward scientific answer to the sunset question, but that’s not the point. It’s the emotion of the sunset and the aesthetics of witnessing the beautiful that concern this questioner.

Here we can emphasize that aesthetics is not part of scientific inquiry. The question faults science for not explaining the feeling of a sunset, but that’s not what science attempts to do. One’s subjective opinions and feelings are simply not part of science, in the same way that art and music are not scientific concerns. Not everything humans do is comprehensible in terms of repeatable, controllable tests using double-blinds, though for those questions that can be addressed this way, the process of science does a bang-up job of answering them.

And even if we have good scientific explanations for sunsets, this does not preclude people viewing them in other terms. My colleague Peter Hess has noted:

I sense no contradiction between accepting sunsets and moonlight as explainable by scientific principles indifferent to human needs, and at the same time believing that they participate in a mysterious intentionality emanating from the ineffable divine.

Asking how can sunsets be explained without God is therefore a problematic question, one that disintegrates upon closer examination into vapid meaninglessness.

These questions remind me of an ACLU lawsuit recently filed against Negreet High School in Sabine Parish, Louisiana. As part of a pattern of proselytizing at Negreet, a teacher at this pubic high school set this test question: “ISN’T IT AMAZING WHAT THE ______ HAS MADE!!!!!” The only acceptable answer was “Lord”; moreover, students who wrote any other answer were humiliated in front of the class by the teacher.

Reading this should make you angry. And yet this is exactly the sort of thing that happens in classrooms all across this country. Public facilities and public monies are appropriated to promote a single religious view; teachers commandeer classrooms as their personal pulpits. Not only can this harm the emotions of children—as in the case above—but it does real damage to the education of everyone.

In the end, what does it matter what questions the Buzzfeed creationists ask? We can gain an insight into their thinking, but I doubt reasoned responses will make much headway in changing minds. Instead of wasting time pondering such questions, the creationists should be asking themselves how many kids they’re willing to humiliate in class, how many science lessons they’re willing to destroy, how many jobs they’re willing to give up to more scientifically-savvy workers in other countries. Those are the questions that matter.