Check out our entire series explaining the science involved in the coronavirus pandemic. Sign up to receive our coronavirus update each week.

You know that moment in horror movies when someone is about to do something really stupid and you start yelling at the screen: “Don’t go in the basement!”?

Well, that’s sort of how epidemiologists are feeling about Thanksgiving this year. Because the coronavirus is so widespread right now, and because we’ve learned so much about the main ways it spreads, public health experts worry that traditional Thanksgiving gatherings will be a massive accelerator of the pandemic. So this week, we’re going to revisit a topic we’ve covered before: risk budgets. I hope this will help you—and your students and their families—make wise decisions about how to spend your holidays.

I apologize in advance that this article is going to be something of a buzzkill.

What is your Thanksgiving ritual? In my family, we try to get everyone to the same place. That means combining households from Texas, Washington state, California, and two places in Colorado. We spend the whole long weekend together. On Thanksgiving itself, we all start gathering around mid-morning. Puzzles are assembled, board games are played, football games are watched, snacks and beers are consumed, food is collectively prepared. Sometimes, weather permitting, walks are taken or soccer games played. Finally, we sit down for the big meal. Much friendly arguing, talking over each other, and riotous laughter ensue—for hours. It is really, really fun.

It is also practically a foolproof recipe for spreading the coronavirus. So it is not happening this year. No one is traveling anywhere. We’ve all agreed to find a time to play games together online, but that’ll be it. It’s a huge bummer, but even with all the risk-reducing tricks I have up my sleeve, it just wouldn’t be worth traveling thousands of miles for the kind of Thanksgiving gathering it would be safe to have.

I thought it might be worth taking you through my family’s risk-assessment process so you can see how we came to that decision and perhaps follow a similar process yourself.

You might recall a pair of articles I wrote back in May 2020 about “How do I decide what’s safe”: Part I: Assembling your tool kit and Part II: Using your tool kit. In them, we learned how to assess the risk of becoming infected in any given situation by examining five factors:

- How big is the space you’re in and how many people are in it?

- What’s that space like?

- How long are you spending in that space?

- What are you doing in that space?

- How likely is it that there’s an infected person in that space?

Back in May, it was already suspected that the virus spread most efficiently indoors, especially in crowded spaces with poor ventilation. The longer people gathered and the more talking, laughing, singing, or shouting they did, the higher the risk. Since May, it has become clear that this kind of environment is responsible for the vast majority of transmission.

To give you an idea of the odds, a study published on November 6, 2020, found a household secondary attack rate of 53%. What does that mean? It means that when a symptomatic individual tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 (these were considered the index cases), over half of that person’s household members tested positive within the next seven days. Indeed, about half of the index cases’ household members tested positive immediately, suggesting that they had been infected before the index case showed symptoms, or possibly that the index case wasn’t actually the first person in the household infected.

Given those odds, an indoors Thanksgiving gathering taking place over multiple day would be a very high-risk event if even one person was already infected with the virus.

Now we have two choices: either find a way to assure ourselves that no one is likely to be infected or change our behavior to reduce the risk of transmission if someone is infected.

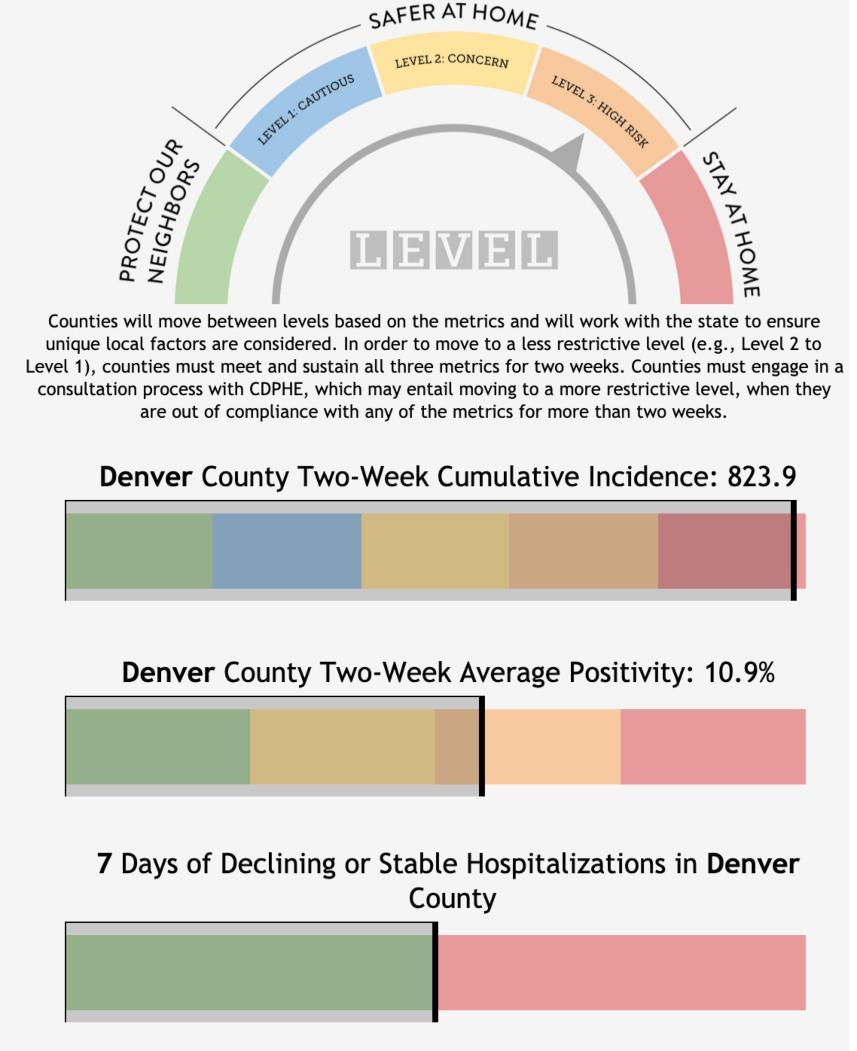

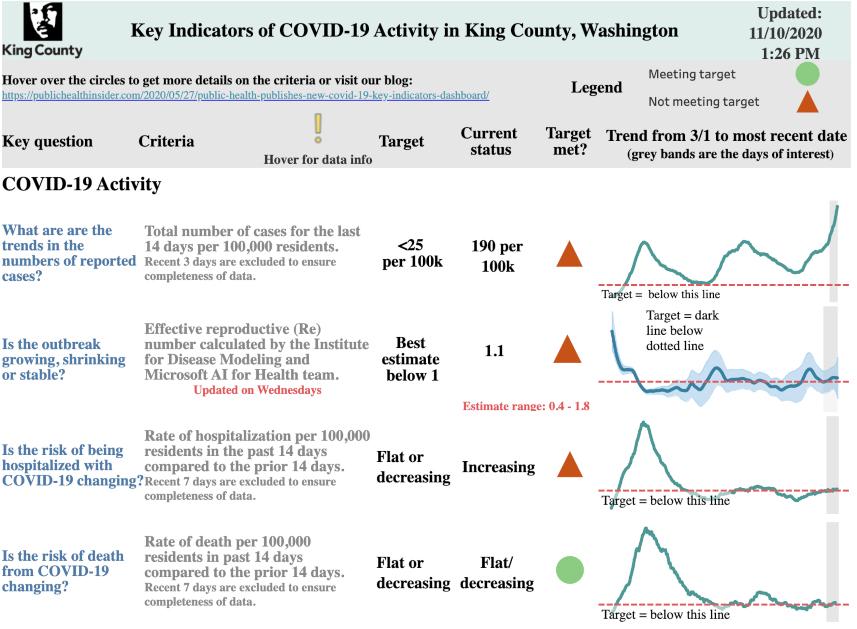

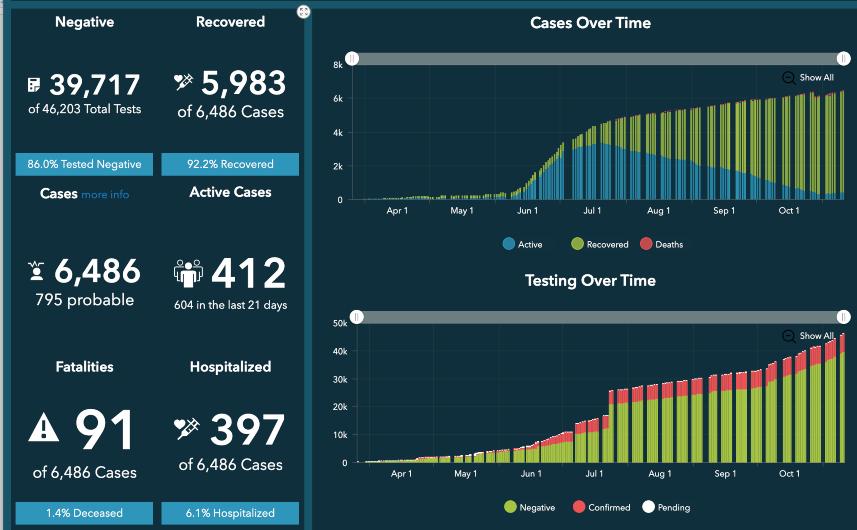

I mentioned that my family is far-flung. They’ve all been pretty careful, but they all do venture out to grocery stores and the like. Plus one is a personal trainer still seeing clients, one is in graduate school and attending some in-person classes, and one couple is part of a family bubble of 5–6 other people from several distinct households. So the risk that one of them is infected is not zero. Just how far above zero depends a lot on how widespread the virus is in their communities. I decided to see what their local numbers looked like.

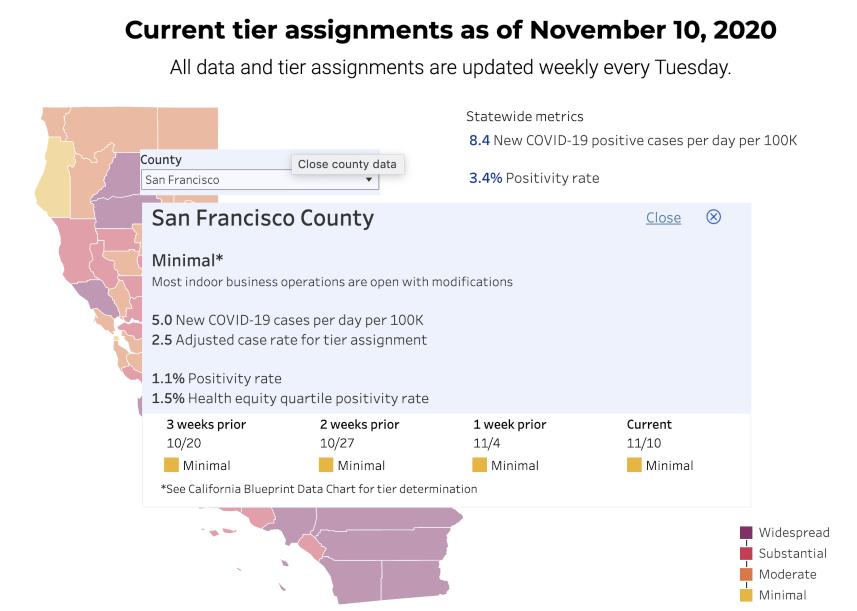

You may not be surprised to hear that the availability of information varied considerably from place to place, since no national framework has been put in place for assessing and reporting local case and testing data. Here’s what I found about San Francisco, where my husband and I live: