Here’s how we’re going to play: Divide your class, if you’re still teaching, into teams of 3-4 students—you’ll need a set of Pick Up Sticks for every two teams. Or divide your family into teams. If you’re all by yourself, you can just consider the first round practice. You’ll divide yourself into two teams for the second round.

Round one: Flip a coin. The winner goes first. Take turns picking up one stick at a time, without causing another stick to move, otherwise you lose your turn, until they’re all picked up and tally the score—one point for each stick removed.

Round two: The team that won the first round gets to go first. The losing team now has to play using their non-dominant hand. Right-handers must use their left hand, left-handers their right. If you’re playing alone, divide yourself into Team Right Hand and Team Left Hand.

Round three: The winning team goes first again. The losing team now has to play using their non-dominant hand and with one eye closed.

Round four: The winning team goes first again. In this round, the winning team gets two chances to remove a stick should they move a stick on their turn.

How’s it going? Is everyone having fun? Does this game seem fair?

Not fair at all, right?

Playing this new version of Pick-Up Sticks is one way to understand why some groups of Americans are being infected by and dying of COVID-19 at so much higher rates than other groups: some groups face considerable disadvantages when it comes to risk factors for serious illness or death. The numbers are grim.

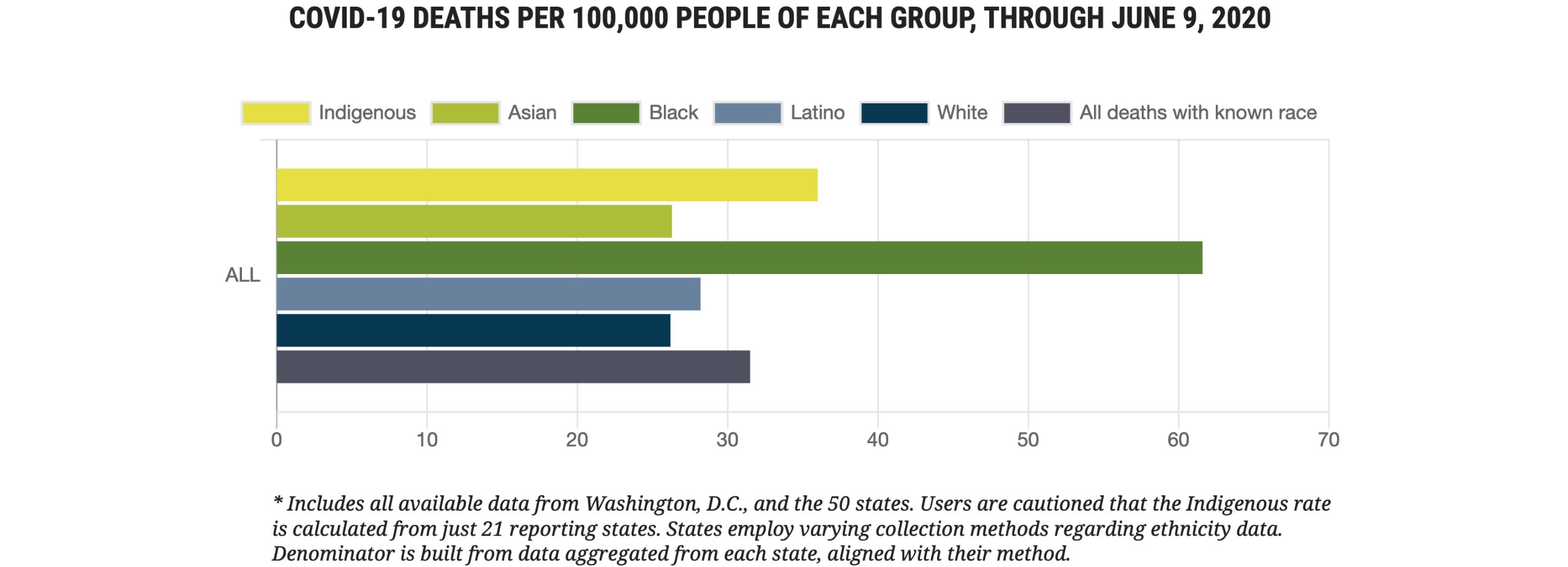

As reported by the APM Research Lab, which aggregated data from all 50 states and the District of Columbia, as of June 10, 2020:

- 1 in 1,625 Black Americans has died (or 61.6 deaths per 100,000)

- 1 in 2,775 Indigenous Americans has died (or 36.0 deaths per 100,000)

- 1 in 3,550 Latino Americans has died (or 28.2 deaths per 100,000)

- 1 in 3,800 Asian Americans has died (or 26.3 deaths per 100,000)

- 1 in 3,800 White Americans has died (or 26.2 deaths per 100,000)

In other words, Black Americans are more than two times more likely to die of COVID-19 than White, Asian, or Latino Americans, and Indigenous Americans are nearly 50% more likely to die than White, Asian, or Latino Americans. Experts point out that although the overall mortality rate among Latino Americans is similar to that among Asian and White Americans, Latinos are disproportionately likely to become infected (in 14 states, Latinos represent three times more cases than their share of the population; in another 17 states, Latinos represent twice as many cases than their share of the population). The Latino population is significantly younger than the other groups, so there are fewer individuals in the highest-risk age groups, which leads to the lower mortality rate.

Why is this happening? It’s kind of like that game of pickup sticks we began with. It’s hard to win a game with even one disadvantage, like never getting to go first. Playing with your non-dominant hand makes it even harder. If you have a lot of disadvantages, winning becomes practically impossible.

When it comes to dying of COVID-19, there are distinct disadvantages that increase your risk.

First, factors that increase your risk of being infected by SARS-CoV-2:

- Being an essential worker who cannot work at home

- Working under crowded conditions

- Sharing living quarters with many people, especially of multiple generations

- Living in a dense community

- Relying on public transport

- Lacking access to public health information in your native language

- Lacking access to running water

Then, factors that increase the risk of serious illness or death if you are infected:

- Age—the older you are, the higher the risk

- Pre-existing conditions such as heart or lung disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, obesity, or suppressed immunity

- No health insurance

- No paid sick leave

- Lack of proximity to healthcare services or essential businesses like grocery stores or pharmacies

- Poor air quality

When you consider this list of factors, it becomes pretty clear why the mortality rates are so different—Black, Indigenous, and Latino Americans are much more likely to fall into at least one, if not many, of these categories. I’ll give a couple of examples, but it would be illuminating for your students to divide up into teams to research the percentage of people in different groups who fall into each category.