Check out our entire series explaining the science involved in the coronavirus pandemic. Sign up to receive our coronavirus update each week.

In early April 2021, I told you about a conversation with a vaccine-hesitant friend where I learned a lesson about putting aside my penchant for piling on the facts in favor of asking questions and identifying shared values.

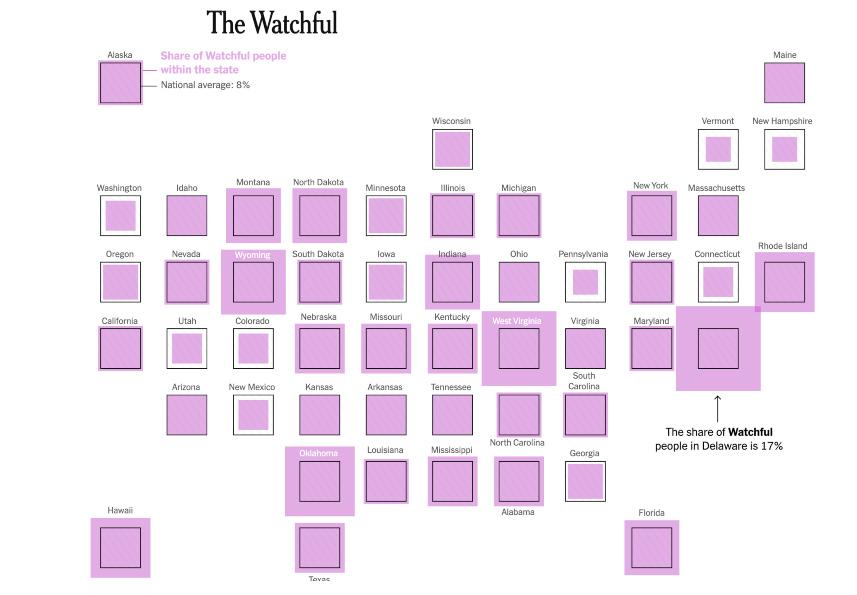

As a brief extension of that idea, I point you toward two excellent resources. First, a recent New York Times article entitled “Meet the Four Kinds of People Holding Us Back from Full Vaccination.” The author makes the crucial point that there are several reasons why people might be turning down vaccines. In the article, the vaccine-hesitant are placed in four categories. Before having your students read the article, it might be interesting to ask them to write down all the reasons for vaccine hesitancy they can think of. Then they can compare them to the categories in the article:

Watchful: people who aren’t opposed in principle, but don’t want to be the first to get the vaccine.

Cost-anxious: people who are worried about missing time from work to schedule a vaccination or because of side effects that might keep them home for a day or two.

System distrusters: people who for one reason or another don’t trust authorities, which could be medical authorities, political authorities, or corporations.

COVID doubters: people who don’t think COVID-19 is real or dangerous to them. (The Times described them as “skeptics,” but this isn’t a good usage because a healthy skepticism is part of the scientific attitude.)

By the way, this article has really great infographics showing the prevalence of these different kinds of vaccine hesitancy in all fifty states. Here’s the one for the Watchful category: