Check out our entire series explaining the science involved in the coronavirus pandemic. Sign up to receive our coronavirus update each week.

When I wrote about the question "How Will We Know if Social Distancing Is Working?" on March 27, 2020, there had been 2,110 deaths from COVID-19 in the United States. As of today, May 1, 2020, there have been over 62,000 deaths. So, certainly for tens of thousands of families who have lost loved ones, social distancing didn't work. Or, more accurately, it didn't start to work soon enough.

Those numbers are sobering. But it is widely agreed that the situation would have been dramatically worse with no social distancing at all.

We'd like to be able to answer two questions about social distancing. One is theoretical and not urgent: How much worse would it have been without social distancing? The other is practical and urgent: How can we tell we're ready to reopen?

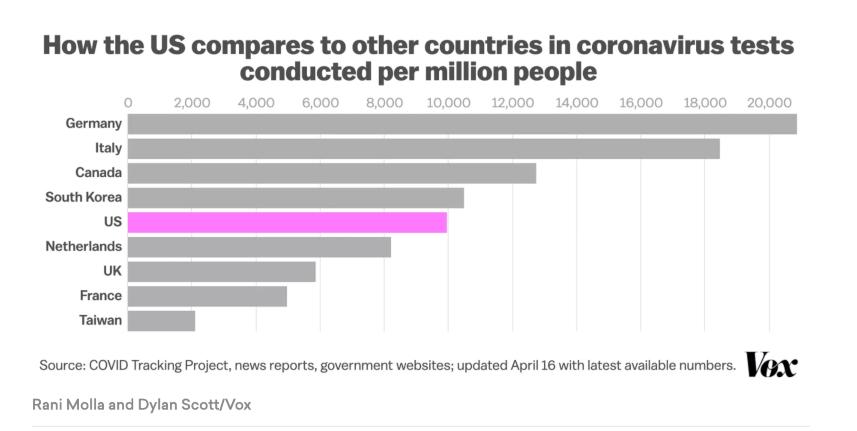

The questions are very much related, and determining the answers is complicated. But the bottom line is: the United States is still not doing enough testing to make evidence-based policy choices about whether to reopen the economy or stay locked down. The number of cases and deaths seems to have begun to level off or decline in many parts of the US, and social distancing seems to have been a big part of making that happen. But what we don't know is whether the current restrictions are keeping a lid on a pot of water that is still at a full boil or whether the water is now simmering gently. And we don't know that because we’re just not doing enough testing.