Check out our entire series explaining the science involved in the coronavirus pandemic. Sign up to receive our coronavirus update each week.

No more than a couple of hours after the Washington Post published this article about the efficacy of various masks, an NCSE staffer posted on Slack (yes, of course we have a Slack channel at NCSE; how did you think we communicate, semaphores?):

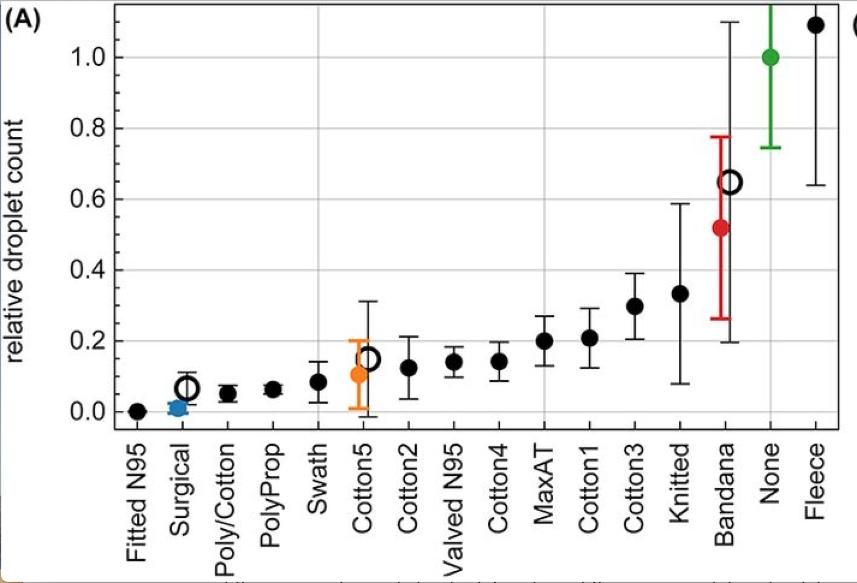

“Turns out, the gaiters [my spouse] wears on her morning walks and during our hikes break up her large particles into small ones, that linger longer in the air. Thank goodness she hasn't been sick, because she would have been spreading the virus. All those runners/hikers/bikers need to switch to the thicker cotton fabric masks, which is tough because it's really hard to breathe through them during exertion.”

If a savvy NCSE staff member was alarmed by the Post’s story, we can be sure that lots of other people were too. Arguably, the whole point of the article (or at least the headline) was to alarm — even though, as it turns out, the researchers who did the study never claimed that their work should be considered definitive about how well different masks stop the spread of the coronavirus! The researchers did, however, indulge in some speculation that got out pretty far ahead of what they’d actually shown.

Reading the introduction to the research study with your class, then following up by examining some of the articles reporting on the study in the popular press, makes for an excellent exercise in thinking critically about media coverage of science. In addition to the Washington Post article cited in the first paragraph, here is a follow-up article written by same reporter. And here is a more deeply reported discussion of what the original research study actually showed.

I do want to pause for just a second to insist that my intention is not to bash science journalists. Science journalists do our world an immense service. However, sometimes the desire to make research results sound more exciting, or more definitive, or more controversial than the results justify lead both reporters and scientists to focus on the “newsiest” finding, even if it’s not the strongest finding. That’s why it’s so important that students learn to read science coverage critically. And boy-howdy does this story ever illustrate the problem.

First, the original Washington Post headline: