As cities move beyond recycling paper and metals, and into glass, food scraps and assorted plastics, the costs rise sharply while the environmental benefits decline and sometimes vanish. “If you believe recycling is good for the planet and that we need to do more of it, then there’s a crisis to confront,” says David P. Steiner, the chief executive officer of Waste Management, the largest recycler of household trash in the United States.” (The Reign of Recycling)

I put the newspaper down on the table, enraged. After years of work and a young career built upon an accidental passion for waste management, I wondered: was The New York Times contributing columnist John Tierney trying to tell me I was wrong, that recycling was bunk, and landfilling our waste would be better for our environment? Despicable.

Tierney’s argument is primarily economic, which, I idealistically concluded, missed the point. But (said the creeping doubt in my brain) what about the impact of recycling on climate change? Particularly the effort and energy used to sustain growing municipal recycling programs. Did Tierney have a point? Would it really create fewer emissions to bury that trash in “rural areas” as he suggests? Five years later, in the midst of my second graduate degree in environmental science, I grudgingly admit that the issue is complicated. Recycling is not a golden ticket to sustainability, despite what we’ve been told as a society, just as replacing all our incandescent light bulbs with LEDs won’t help us achieve the carbon reductions outlined in the Paris Agreement. Our societal dependence on carbon permeates every aspect of 21st-century life, from how we travel, to how we eat, to the waste we generate and what becomes of it. It is increasingly clear that large-scale, structural change will be necessary to pivot human society toward sustainability, especially if we are to maintain behaviors and habits that have come to define our “quality of life.” What does this imply about the value of individual action, especially individual action not directed at climate change? Is there value in environmental programs (like recycling) that are popular and individually empowering, and which embody principles of sustainability, even if they are inefficient? Or do they reinforce behaviors of consumption and disposal?

In academic environmental science (and increasingly in popular culture and politics), climate change is the topic. As the fundamental environmental issue of our generation, everything from funding proposals to international policy must be justified within the context of climate change. It is a global problem, reflecting the interconnectedness of our global society, and its solution will require global collaboration, flexibility, and courage to try new things. Cutting emissions will be no easy task, and consensus on how to achieve the necessary reductions to protect future generations from catastrophic environmental and humanitarian crises is absent. Solutions fall into categories that range from polarizing to paralyzing. Because climate change is slow and repeatedly overshadowed by more pressing human crises, initiatives to address it are continually postponed — principally by older people in positions of power. Meanwhile, existential panic grows and intensifies in the younger generations that will live to see the consequences of political inaction. Next to the panic dwells uncertainty — which actions matter for climate change mitigation and how much do they matter? As a soil ecologist, I struggle with this question. Should I drop everything and go protest, or does my research contribute to the mosaic of climate change solutions, too?

In the era of climate change, how should we think about other environmental issues? Does everything relate back to climate?

In a sense, everything does relate back to climate. We have seen that in the comprehensive nature of legislation presented to address climate change and promote economic recovery in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic (legislation such as the Green New Deal). We can’t talk about climate change without talking about health, safety, and justice, and we can’t address species and landscape conservation while people lack housing, economic security, and reliable energy. Everything is connected, as any good ecologist knows.

Solid waste and refuse management are part of the climate conversation, too, even if the carbon savings associated with best practices are tiny percentages of what the global community must eventually eliminate. If we are to live sustainably through the 21st century, use and expenditure must be decoupled from models of economic growth, and there must be a valuing of the natural capital, which humanity has used and abused for too long without consequence. The destruction of the atmosphere via greenhouse gas additions illustrates the concept of the tragedy of the commons, wherein a shared resource is exhausted because of unregulated and/or careless overuse. Atmospheric pollution by carbon-based waste products (such as carbon dioxide and methane) is also a gaseous analogy of what poorly managed trash can do to an ecosystem.

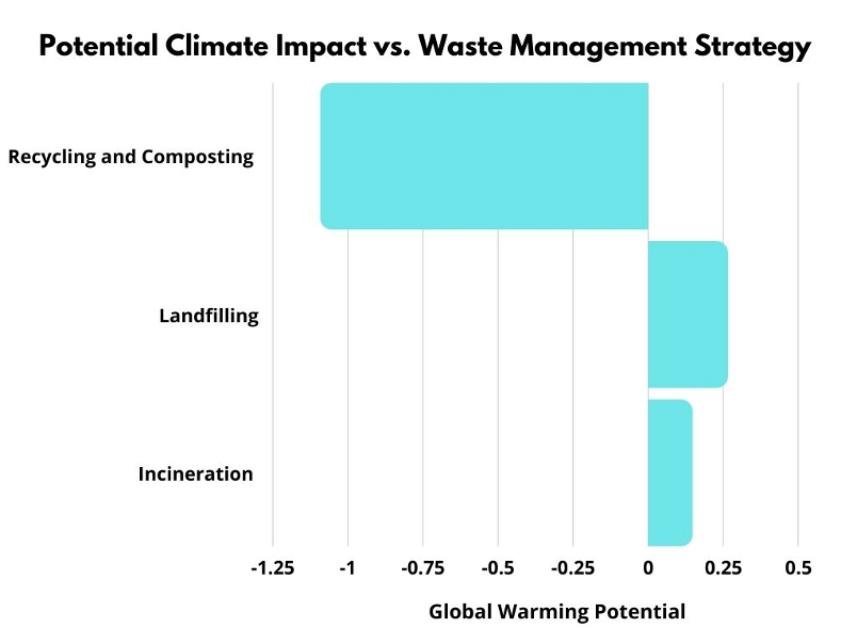

Admittedly, the recycling question is complex. Although it enjoys an almost universally positive reputation, in practice, recycling is often expensive, inefficient, and ineffectual. People fundamentally misunderstand several aspects of recycling (including what to recycle and what is most important to recycle). Recycling programs can also reinforce consumption behavior that is antithetical to climate change mitigation by greenwashing our culture of consumption and disposal. Yet recent research shows that recycling as a waste management strategy is climate friendly — especially compared to landfilling.

What is also increasingly obvious is that waste in the context of climate change requires an understanding of scale. Like so many environmental issues, waste management is intertwined with other societal issues, such as energy security, environmental justice, community health, history, and the geographies of systemic inequalities in access, awareness, and inclusion. Effective waste management will primarily support climate change mitigation efforts as part of a cohesive, systemic approach to sustainability. The circular symbolism of recycling; its participatory, civic nature; and its role in protecting natural areas from extraction and landfilling are just as important — if not more so — than its carbon savings. But that doesn’t mean recycling is not part of the climate solution. The crucial caveat is that waste materials are extremely heterogeneous and some are not appropriate for traditional recycling (one of Tierney’s strongest points, to his credit).

The Materials Conundrum

When comparing the relative carbon cost of different waste management strategies, one of the most confounding issues is the diverse nature of our discarded materials. From a decompositional perspective, wood behaves very differently from scrap metal, and both are unique from plastics and organic materials. In recent years, this has resulted in a patchwork of complex recycling systems across the country and the world (in areas with sufficient budgets). In Yokohama, Japan, residents sort refuse into 10 subcategories to facilitate its “correct” management. Berkeley, California, once had seven categories for trash (now it has three). Pre-pandemic New York City had four regular categories of curbside trash plus coordinated local drop-off events for materials like hazardous waste, electronics, and Christmas trees. The driving forces behind collection programs are often sociopolitical: recycling tends to be popular, and in areas where program participation is high, residents are often fiercely proud of the initiative. Participation is a communal commitment. On the other hand, programs are expensive, often both financially and climatically (different wastes require different trucks, different drivers, and different routes). Furthermore, work at facilities can be difficult, especially when compliance is lacking and materials are contaminated or require additional labor to re-sort.

For the most part, recycling is a more climate-friendly option than landfilling, but that doesn’t mean that ten-bin systems are our future. Not all garbage is created equal, after all. Some waste is made to be recycled, while other waste simply isn’t worth the investment in extra trucks and infrastructure. Among the best recycling candidates are metals, especially those of the non-ferrous variety (aluminum, copper, zinc, etc.). The energy savings from avoidance of primary extraction, refining, and transportation makes metal the perfect material for recycling, so much so that recycling plants will buy metal waste from you. In some cities, metal recycling is an informal economy in and of itself. Glass is also perfect for recycling, although its fragility and weight can make it harder to transport and protect than metal, resulting in lower carbon savings. Both metal and glass can be recycled indefinitely.

Paper is also a great candidate for recycling. Paper production, not to mention taking stored carbon (i.e. living trees) out of the ground, is very energy-intensive. Recycled paper production can be half that costly. By recycling paper, you also prevent it from decomposing in the landfill and releasing carbon rich greenhouse gases to the atmosphere. Unfortunately, paper can only be recycled about 5 times before it loses its integrity.

Food and plastic, on the other hand, are complicated. For plastic, much like trash in general, compositional heterogeneity impedes material processing. Different plastics behave differently and their varied compositions make some of them reasonably good candidates for recycling, with many others virtually impossible. Overall, however, plastics are less energetically costly to produce from scratch than to recycle. Food is also tricky. Recycling food waste, via composting, helps return organic carbon to the soil system and can facilitate soil carbon stabilization via microbial processes. Composting produces a good deal of carbon dioxide, but it is more climate friendly than landfilling, in which decomposition occurs in oxygen-poor environments and produces methane, a greenhouse gas approximately 30 times more powerful than carbon dioxide, as a waste product. However, limited composting is not the reason food waste has become a climate issue. Crucially, the carbon emissions associated with food waste have less to do with final disposal strategies than with waste created along the supply chain.

In itself, recycling is not a solution to our climate problem, but its carbon footprint is better than the alternatives for waste management. However, maybe Tierney had a reason to be critical of the ever-expanding recycling infrastructure and corresponding budgets to get at every possible category of waste. Arguably, there is no need to drastically expand the system, if you are getting the major contributors (metals and papers). For the foreseeable future, we can expect some materials to be non-recyclable. This disrupts the increasingly popular “zero waste” goals of many cities, as many rely on recycling in their strategic plans. However, by focusing on the most important materials, there may be a chance to make recycling economically, as well as climatically, feasible.

Recycling as a Pathway to Environmental Climate Literacy

New York City is currently cutting services in light of the economic devastation wrought by the global pandemic, and one of the more publicized cuts is the residential composting program. SAFE disposal events (where people can drop off harmful products, chemicals, and electronics) are also paused through June 2021. People, including my parents, feel a sense of loss for the program and guilt for throwing their organics in the trash. Rather than succumb to convenience, they’ve now set up their own small-scale operation and are continuing to compost. Although I don’t currently compost in my Harlem apartment (and believe me, I feel guilty about it), I am an obsessive waste sorter. Even when there is no easy access to recycling, I group cans and bottles at the end of an excursion and arrange them in piles for easy recycling — just in case someone with access happens to come across them. When I lived abroad, I hoarded recyclables because I couldn’t bring myself to throw them away and developed a repertoire of crazy art projects that I did with kids to “salvage” them.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given people’s strong opinions about recycling and associated programs, recycling has been studied repeatedly in reference to behavior change. It is an interesting case study of human belief, intention, and will. While I may take trash to unreasonable extremes, I’m certainly not alone in my enthusiasm for the blue bin. People who recycle tend to love recycling, perhaps because it is an easy way to practice civics and participate in socio-cultural tradition. The philosophy behind recycling (and illustrated by its symbol, the three arrows circling into each other in a repeating loop) is compelling: circularity, connectedness, something old becoming something new. Participation makes people feel good.

Interestingly, recycling has been described as an altruistic behavior, suggesting that it is more social than individual in purpose. Studies have also found that participation is positively affected by peer behavior — family and friends who recycle or block leaders who promote the program — as well as by education/awareness and internal motivations. There is always a limit to altruism, however. The easier recycling is, the more likely people will participate; the inconvenience of sorting, storing, and transporting recyclables proves to be a deterrent to participation, as does the lack of understanding of the purpose and logistics of the system.

If structural barriers are the most significant factor for determining participation in recycling programs, as concluded by Derkson and Gartrell in their 1993 study, it may help explain why the United States recycles at a rate of only 35% — lower than most other developed countries. It also might explain the sluggishness of the domestic industry. Our recycling infrastructure is undeveloped because for years we’ve outsourced the process by selling recyclables to China. Right now, we don’t have an endpoint for our recyclables, despite the fact that many municipalities continue to collect them.

In addition, our secondary materials are poor quality because many Americans don’t sort correctly. In the absence of a national system, recycling in the United States is confusing, to say the least; rules, signage, and materials vary from place to place. Many people rely on the universal recycling symbol (those little numbered triangle codes) that appears on containers and packaging to determine how to dispose of it. In actuality, that symbol means only that the material is technically recyclable — it doesn’t mean your city actually accepts it for recycling. Often your city will only accept very few items that are technically recyclable. Even avid recyclers engage in aspirational recycling, where we optimistically toss items we’re unsure about into our blue bins, hoping that they might be recyclable. What many of us don’t know is that in so doing, we contaminate the whole load. This contamination is exactly the reason China stopped buying our materials, and it will impede the development of our own nascent recycling industry.

Attempting to understand behavior change in relation to climate change provides an interesting comparison with recycling. Climate change is abstract in many ways, and despite evidence of its acceleration, many people still do not understand how it relates to them, personally. This can make action seem less urgent. The moneyed interests that influence our politics cultivate this misplaced tranquility. There is also widespread misunderstanding about the dynamics of climate change and the actions that are most effective for combating it; the moneyed interests cultivate these misconceptions, too. For example, a 2009 study found that when respondents were surveyed about personal behaviors to mitigate climate change, instead of mentioning energy reduction (which was explicitly emphasized as a good strategy via government PSAs), many people mentioned recycling.

This is problematic if people are misplacing their efforts towards combating a serious global problem. Another potential problem is messaging. There is a compelling argument that by promoting recycling, people are less conscious about consumption and disposal because the illusion of recycling convinces us that the behavior is neutralized. Ingmar Lippert (2011) argues that recycling may be unsustainable behavior in that it maintains the hegemonic capitalist system of consumption and disposal. In the end, he claims, it is sustainable neither materially or socially, and a modernization of the structures and systems simply allows the continuation of the same society that caused environmental catastrophe in the first place.

But even if recycling won’t solve our climate problem, does that mean it should be abandoned? Would canceling recycling programs help reduce our consumption behavior? The idea of pushing for reductions in recycling service or of removing items from collection programs can be deeply unpopular. There are even cases of people protesting when recycling programs have been shut down for budgetary reasons. The results of the Whitmarsh study suggest that even if people are misplacing their climate change efforts, they are still proudly participating in a mitigation campaign. Anecdotally, I’ve noticed the same passion for recycling among my students at the City University of New York and among community members I worked with in Latin America as a Peace Corps Volunteer.

Clearly, we need to do better. We can start by removing structural barriers to participation and by promoting our developing industry. We also need to do better with messaging, because recycling should become the “R” of last resort. Reduction of waste, and consumption in general, should be our primary goal, along with reuse. Development of clean fuel and energy will determine whether recycling can be sustainable in the end. As important as correct waste management is for the environment and our psychologies of Earth stewardship, this is not a primary climate strategy — rather, it will contribute to an integrated, multifaceted plan for sustainable human societies.

Recent Research

From a climate point of view, Tierney is wrong about landfills. A recent study found that when comparing landfilling to incineration and recycling, landfilling generated more greenhouse gases than the other two scenarios, with recycling consistently outperforming the other options (Figure 1). Moreover, incineration is a better option than landfills even without considering the fossil fuel usage that waste to energy production might offset. In almost all cases, recycling saves carbon, though the savings can be quite different depending on the material being recycled, with metals bringing the largest savings. For materials that are more difficult to recycle, incineration is more efficient than landfills for capturing and using greenhouse gases. The study does not consider transportation to, and operating costs of, recycling plants, incinerators, and landfills in its calculations.