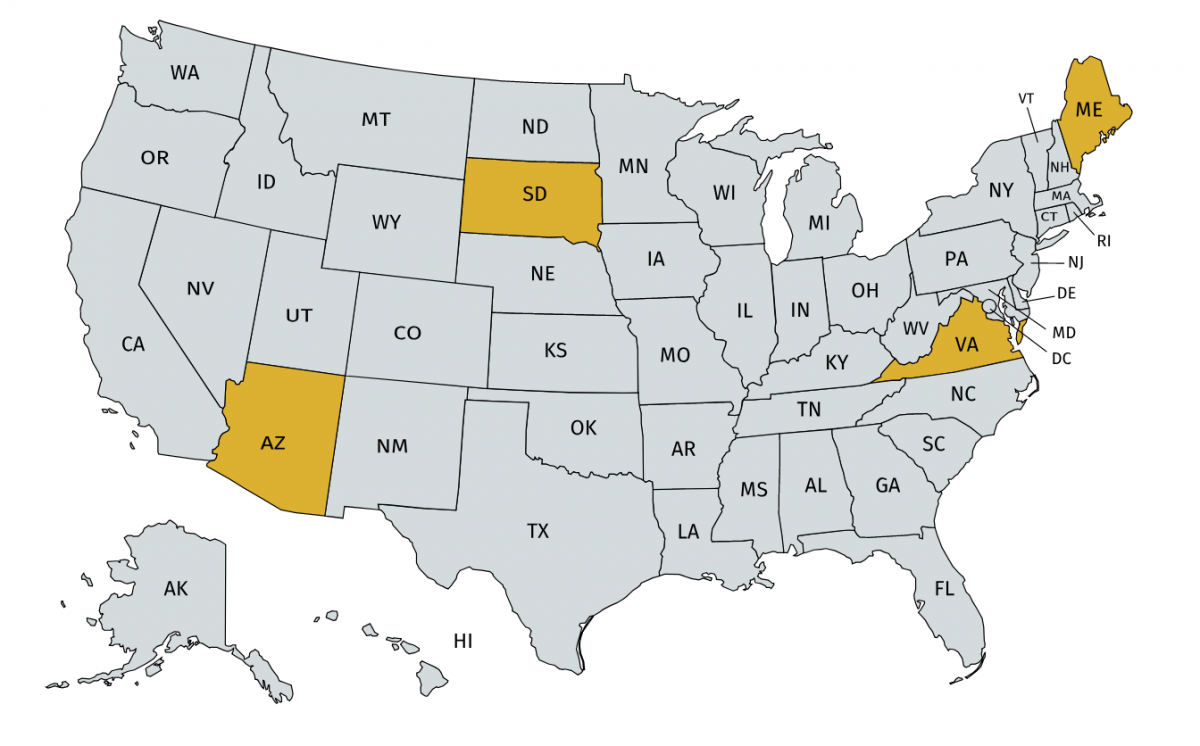

Politics, as the saying goes, makes strange bedfellows. But if a handful of state legislators in Arizona, Maine, South Dakota, and Virginia had gotten their way this year, public school teachers in their states would have found that politics also makes strange science lessons.

Politics, as the saying goes, makes strange bedfellows. But if a handful of state legislators in Arizona, Maine, South Dakota, and Virginia had gotten their way this year, public school teachers in their states would have found that politics also makes strange science lessons.

Five measures under consideration in these four states in 2019—Arizona’s House Bill 2002, Maine’s House Paper 433, South Dakota’s House Concurrent Resolution 1002 (PDF) and House Bill 1113 (PDF), and Virginia’s House Joint Resolution 684—would have required or urged the adoption of a code of ethics for public school teachers, purportedly to prevent them from engaging in “political or ideological indoctrination.”

If these anti-indoctrination measures sound like a solution in search of a problem, it’s because they are. Despite a handful of ballyhooed counterexamples, it’s rare for teachers to engage in indoctrination. They are trained, after all, to educate. And even with regard to socially controversial issues, surveys indicate that, for good or for ill, teachers tend to teach in accordance with the mores of their communities.

Unsurprisingly, the backers of these anti-indoctrination measures rarely offered any evidence that there is a problem. The sponsor of the Arizona bill, for example, claimed that he introduced it after he was “inundated” by complaints about teachers from parents. But a public records request from the Arizona Republic revealed that he received just a single e-mail from a parent—after, not before, he introduced his bill.

And there are already policies and procedures in place to govern teacher conduct in the classroom anyhow. The Arizona bill, for example, would have forbidden public school teachers from expressing a view on pending legislation while on the time clock. But that’s something that is already forbidden by Arizona law, and two Arizona teachers were (controversially) disciplined for violating the law in 2018.

Importantly, the cure would be worse than the disease. In trying to prevent teachers from engaging in indoctrination, these anti-indoctrination measures all prohibit advocating for any side of a controversial topic, where controversial topics are defined as those addressed as part of a local, state, or political party’s platform. (The wording differs a little from measure to measure, but the thought is the same.)

So these measures assume that a topic is controversial if it is addressed in a political party’s platform. That assumption doesn’t survive even the briefest encounter with reality. The 2018 platform of the South Dakota Democratic Party, for example, recognizes (PDF) “the importance of agriculture … as the source of healthy, wholesome, affordable supply of food and fiber for our citizens”: this is controversial?

The problem is accentuated when it comes to the two scientific topics that are most often the target of misguided legislation involving public education: evolution and climate change. These are mentioned in the platform of a handful of state political parties. For example, the 2018 platform of the California Democratic Party refers, correctly, to “the strong scientific consensus” on climate change and evolution.

If a state passed one of these anti-indoctrination measures, then, evolution and climate change would be thereby deemed “controversial”—even though they are not scientifically controversial. Teachers would have been required not to take a stand on them, and to “provide students with materials supporting both sides in the controversy and present those views in a fair-minded and non-partisan manner,” to quote the Arizona bill.

That would conflict, of course, with the state science standards in those five states, as well as with the recommendations of the nation’s top scientific organizations such as the National Academy of Sciences and the American Association for the Advancement of Science, as well as with the position statements of the National Science Teachers Association (on evolution and on climate science in particular).

Whether the sponsors of these anti-indoctrination measures realized the full implications of their provisions is unclear. It is suggestive that seven of the sponsors of both of the South Dakota measures were also sponsors of House Bill 1270, a bill intended to allow teachers to misrepresent science—evolution and climate change in particular—in their classrooms without any oversight from administrators.

It is also ironic. For legislators who approve of the principle that public school teachers should not use their classrooms for political, ideological, and religious advocacy should recognize that evolution and climate change are scientifically uncontroversial. It is only ideologues—whether religious or political—who attempt to stigmatize evolution and climate change as controversial.

Unnecessary, intrusive, and overreaching: there was a lot not to like about these anti-indoctrination measures. But the way in which they threatened to undermine the integrity of science education may have been their worst feature. It was a good thing for them to be put to sleep.