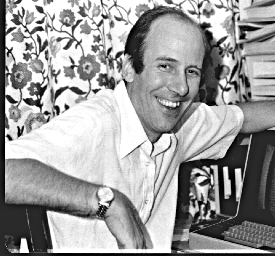

It’s hard to believe that Bob Schadewald would have been 71 today, had he not died much too young in 2000 from cancer. He was on the board of NCSE when I was hired, served as president of the board, and edited our publications. He was a good friend, and I’ve often thought of him over the years, especially when someone mentions something especially arcane from deep in the weeds of “creation science.” Usually I think, “I wonder what Bob would have made of that.”

Probably he would have thrown back his head and laughed good-naturedly, and set to work, whatever the topic—physics, chemistry, biology, geology—explaining why the notion was bad science. Anyone listening would get a friendly and painless introduction to a lot of science; Bob knew a lot of it, and knew how to communicate it. His day job was science and technical writing, and being a smart guy, he could learn what he needed to know to carry out assignments as varied as documenting computer software or explaining complex biomedical devices.

The creationism/evolution controversy was only one of the topics that caught his fancy: he was an expert on the late nineteenth-century flat Earth movement in the US and Great Britain, and also wrote about offbeat movements like geocentrism, the hollow Earth, perpetual motion, and UFOs. He probably tried the patience of his wife Wendy by scouring used bookstores wherever they vacationed, ferreting out obscure books and pamphlets relevant to the pseudoscientific topics he was fascinated by. He maintained an extensive correspondence with other collectors, trading or copying long out-of-print and rare pamphlets and other components of these sometimes zany movements. Many of his writings on these as well as other pseudoscience topics are found in the posthumous collection of articles, Worlds of Their Own: A Brief History of Misguided Ideas: Creationism, Flat-Earthism, Energy Scams, and the Velikovsky Affair, edited by his sister, Lois Schadewald. (David Morrison reviewed it for Reports of the NCSE, recommending it as “a great book for readers of Reports of the NCSE and others embroiled in the evolution/creationism controversy.”)

The first time I visited the house he shared with his wife, Wendy, we walked downstairs to his office, which included the largest personal library I’ve ever seen. I should know how many volumes of books he had (I helped the University of Wisconsin acquire the bulk of his works for their growing history of science special collections), but it wasn’t just the numbers, it was also the content. I could have spent months just browsing all the crazy pseudoscience he had collected. NCSE’s archives also house some creationism/evolution material collected by Bob.

Probably what I most remember about Bob, though, is his kindness and generosity. He attended more creationist conferences than anyone I know, somehow maintaining his sanity, but also his civility and sense of humor throughout. He did not hesitate to correct the abundant scientific misstatements that proliferate at such events, but he did it with a Midwestern geniality that didn’t generate offense. Quite commonly he would go off to have a beer (yes, creationists drink beer—many of them) afterwards, and he maintained a friendly relationship with many individuals whose views he opposed. When Kurt Wise lost a large amount of his creationism/evolution books in a fire at Bryon College, Bob quietly packed up several boxes of duplicates and sent them to Wise so that the latter could rebuild his collection. Books, after all, are sacred.

Being able to separate the person from the views is important, and I have tried to learn from Bob. I’ve also tried to keep a sense of humor about my work, as did Bob. As I wrote in an obituary for Bob in 2000,

Once, after a typically long NCSE board meeting, a group of us had gone out for dinner. Immersed as we were in the creation and evolution controversy, after a few drinks, we started talking about creationist “scientific models”—laughing about the convolutions of data and theory required to accommodate scientific data within a 6-day creationist model. Much of the conversation consisted of “and can you believe that they actually think…?” as we regaled one another with examples of creationists’ apparent ability to believe at least 7 impossible things before breakfast. We were having a pretty good time at the opposition’s expense, when Bob looked up and said, “You know, somewhere, there’s probably a bunch of creationists sitting around a table, drinking beer, and saying, ‘those evolutionists! Can you believe they actually think…?’"

We’re going to miss him.

And I still do.