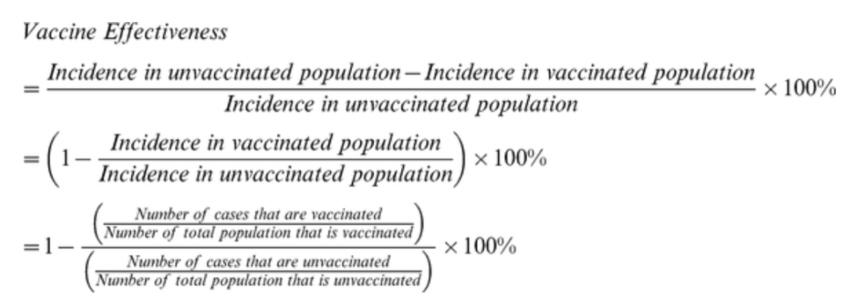

That’s it. Easy-peasy, right?

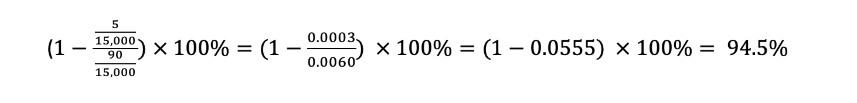

So you can see that the effectiveness number really doesn’t have anything to do with how well the vaccine works in an individual; it’s a measure of how well the vaccine protects the population. But when it comes to infectious diseases, that metric makes sense; if the number of cases is reduced by 95%, the human and social costs of the pandemic are vastly reduced. Especially if the vaccine not only reduces symptomatic illness by 95% but also reduces infection and transmission rates. But that is something these particular trials did not measure.

Here’s the distinction: the “endpoints” used in these trials were symptomatic cases. If anyone in the trial developed a fever, cough, or any other symptoms of COVID-19, they were tested for the virus. As the results show, very few people in the vaccinated arm of the trial (see what I did there?) tested positive. Furthermore, none of the cases in vaccinated individuals was severe, suggesting that the vaccine might shut the virus down quickly. What we don’t know is whether some, or even many, of the vaccinated participants developed asymptomatic infections, possibly generating high enough viral loads to transmit the virus to others.

Whether vaccinated individuals can still spread the virus will be a subject of intense scrutiny as vaccination efforts get underway. It will take many, many months to vaccinate the whole population, and if vaccinated people can still infect others, it will take longer to get the pandemic under control. Most experts, however, seem to think it likely that vaccination will at the very least reduce the odds of transmission. For more on the actual vaccines under development, the differences between them, and how they will be distributed, you might want to have your students check out the December 3, 2020, NovaNow podcast, “Covid vaccines are coming: What’s inside, and how and when you’ll get one.”

It certainly looks like the vaccines from Moderna and Pfizer will play a huge role in blowing away the huge, dark clouds that we’ve all been living under since March 2020. However, it’s not clear whether they’ll mean sunny skies and a 0% chance of rain. More likely, there will be some, not very precisely known, continued risk of spread of the virus until some 60–70% of the population is vaccinated. So, until we know for sure what will be the “Probability of Passing” it on, however, getting vaccinated will not be a “get out of social distancing free” card. Just as with weather forecasts, we’ll have to live with some uncertainty and not throw away our umbrellas and galoshes just yet.