Early morning on Father’s Day, June 17, 2018, I was in Houghton, Michigan, for my summer forestry field research. As I slept, I repeatedly woke to the sound of booming thunder, so deep it felt as though the ground was shaking, and flashes of lightning, so bright it was as though a light switch had been turned on. The rain was supposed to end early in the morning, so I headed toward my field site for the day.

As I drove toward downtown Houghton, I was surprised at how much water I saw along the road. Reaching Michigan Technical University’s campus, I saw that an academic building was flooded, as were parts of the road I was driving on. Wow — definitely a big rainstorm. Steeper roads made the runoff faster and more intense. Okay — a really big rainstorm. As I approached the main street downtown, I stared in disbelief: business owners had simply opened doors on either side of buildings to allow floodwater to flow through. To drive from one end of the downtown to the other, I had to navigate through parking lots and side streets to avoid the surging waters. The flooding was unlike anything I had ever witnessed. I fruitlessly attempted to drive in the direction of my field sites for half an hour before accepting the reality of the situation and leaving for field sites further south.

As it turns out, over 5.5 inches of rain fell from midnight to 6 a.m. What is now known locally as the Father’s Day Flood was officially a 1,000-year flood, meaning a flood of that magnitude is predicted to occur no more than every 1,000 years, based on our historical climate. Though it’s difficult to attribute a single event to climate change, floods and other extreme weather events are becoming more common in Michigan, and in many other regions, as a result of climate change.

And as extreme weather events become more common, they may spark more conversations about climate change, which is increasingly accepted in the United States. Recent 2019 Pew research indicates that in the United States, 83% of people perceive climate change as either a major or minor threat. Extreme events such as the Father’s Day Flood may nudge people to view climate change as a significant risk, since people who perceive themselves to have directly experienced the effects of climate change may be more likely to take it seriously. As an ecologist and science communicator, I’m passionate about engaging with people to have meaningful conversation about climate change. But how can I use local climate change events to communicate effectively with people who don’t believe that climate change is real or human=caused? Perhaps more importantly, how can I motivate people to act on climate change?

Know your audience

To answer these questions, you need to begin with a clear understanding of the audience you’re engaging with — in this case, a person dubious of climate change science. Let’s imagine Sam (a completely hypothetical person), who lives in a mid-sized town and works as a manager at a local business. Sam enjoys going on hikes in nearby forested areas with their dog, reading mystery novels, and cooking. Sam participates in community events, such as bake sales, and enjoys spending time with friends. When Sam encounters news or conversation on climate change, they prefer to disengage from the conversation and think about something else. That’s because Sam isn’t convinced that climate change is real — what’s called “climate change” seems like a lot of different problems, from floods to dying bumblebees to droughts, and that just doesn’t make sense to him. And if climate change is happening, it must be happening somewhere else — certainly not in Sam’s town. Sam never learned about climate change in school, so it must not be a big enough problem to worry about.

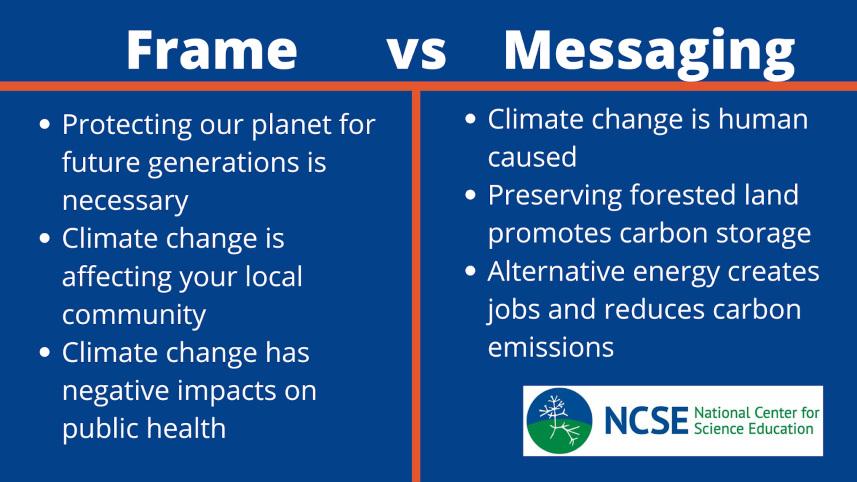

Let’s take a closer look at some of Sam’s beliefs. Sam doesn’t understand why climate change would have anything to do with flooding or bumblebees — doesn’t climate change just mean that the planet is getting hotter? Misconceptions like this one about climate change are a typical communication challenge. Research from the Frameworks Institute outlines some of the most common knowledge gaps about climate change, including the role that humans play in climate change, how climate change works, what impacts climate change will have, and what exactly should be done.

Sam has heard about climate change mostly from their chosen news sources and from friends and family, not in school. Although climate change content is now included in the Next Generation Science Standards, which have been adopted by 20 states and influenced standards in an additional 24 states, climate change is still not thoroughly incorporated in precollege education in the United States. Sam hasn’t had the opportunity to learn about climate change in a sustained and systematic way, and from a reasonably objective and informed source. According to a review of climate change communication by Susanne Moser, the source of climate change communication efforts can have a huge impact on how information is received.