Check out our entire series explaining the science involved in the coronavirus pandemic. Sign up to receive our coronavirus update each week.

How much evidence is needed? That’s a question that scientists have to answer over and over again, no matter what question they’re asking. There’s always a balance to be sought, between detail and precision on the one hand and time and money on the other. The same is true in medicine – is a quick check-up enough, or do the symptoms call for an MRI, biopsy, or overnight monitoring in the hospital? In making every decision, doctors have to weigh the risk of missing an important diagnostic clue against the risk of overtreating, generating a false positive result, or simply overtaxing the medical system.

Such a balancing act is at the heart of current deliberations over the approval of inexpensive, rapid, screening tests into our arsenal of weapons against the coronavirus.

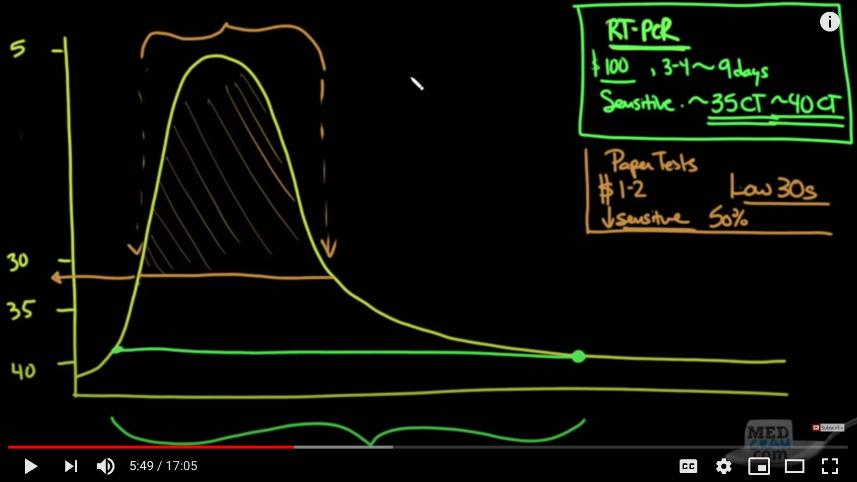

The idea, in a nutshell, is to mass-produce very simple coronavirus tests, much like the familiar home pregnancy tests (except using saliva, not urine), that could be administered at home, as often as daily, with no special equipment. This would help to eliminate the current testing bottlenecks. The trade-off is that these tests would be considerably less sensitive than the clinical tests currently in use. (Remember, sensitivity is the ability to identify true positives, here people who are infected with the virus.) Experts who are advocating for this approach argue that such tests would be sensitive enough to identify people who are shedding a lot of virus and therefore more likely to infect others.

On the face of it, this approach could be absolutely transformative. But there is one big question outstanding: exactly how much less sensitive could these rapid tests be while still being able to detect viral levels that pose a risk to others?

In researching whether this plan would work, I read a lot of papers, talked to an expert, and listened to several interviews with more experts. The most thorough explanation of the idea can be heard on This Week in Virology (a nerdtastic podcast that has been around for years but has become a go-to source of reliable information during the pandemic). But if you want a condensed and extremely clear summary of the idea, the best video I found was this one, from the series MedCram. The full 17 minutes is well worth watching, but the graph below captures the main points.