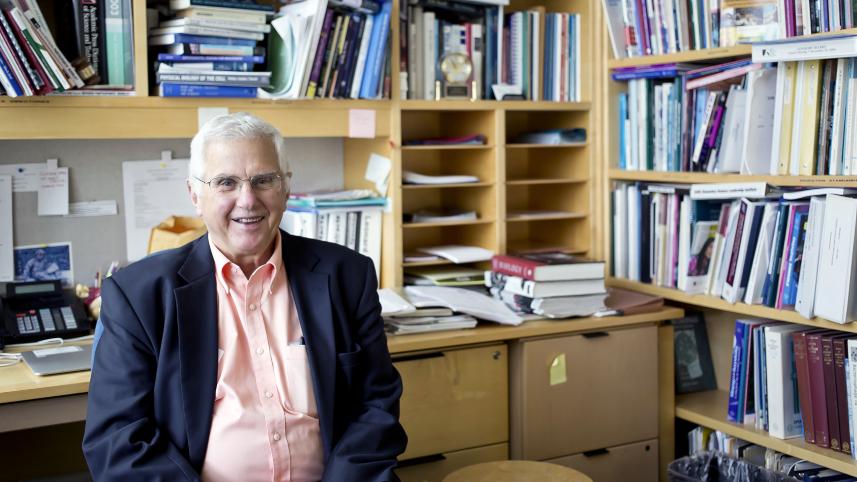

Longtime NCSE member Bruce Alberts is a renowned biochemist with a long list of lifetime achievements. Alberts was awarded the National Medal of Science by President Barack Obama in 2014 and the Lasker-Koshland Special Achievement Award in Medical Science in 2016. Alberts served as editor in chief of Science (2009–2013) and as one of the first three United States Science Envoys (2009–2011). He is now the Chancellor’s Leadership Chair in Biochemistry and Biophysics for Science and Education at the University of California, San Francisco, to which he returned after serving two six-year terms as the president of the National Academy of Sciences. Widely recognized for his work in the fields of biochemistry and molecular biology, Alberts has earned many honors and awards, including 16 honorary degrees. He currently serves on the advisory boards of more than 25 non-profit institutions.

Random Samples: A Conversation with Bruce Alberts

Photo by Christopher Reiger

Paul Oh: In addition to your incredible scientific achievements and policy work, you’ve always supported education. What got you started on that path?

Bruce Alberts: During my second semester biology course, when I was a freshman at Harvard, I was incredibly lucky. By chance, that January of 1957, John A. Moore, then an obscure professor at Barnard College, published his first textbook, called Principles of Zoology. Someone at Harvard had the wisdom to choose that as our textbook. They required that we read the first two-thirds of it, which was a beautifully written history of genetics. It indirectly, through detailed examples, explained the way science is done.

I had never before had any sense of how science actually worked. And it was just thrilling for me to learn that. I became intrigued by such a failure of science education not to get that across to the rest of society. I realized how sad it was that the real life of science is not connected in any way to the schools. And I’m still working on solving this problem

NCSE can move us all—including scientists—to think in more sophisticated ways.

PO: What about your work in support of education are you most proud of?

BA: In 1977-8, I was recruited by Jim Watson for what he envisioned as a critical new textbook that would bring together two important fields: molecular biology, which at that time was fairly new but highly productive, and the much older field of cell biology. Jim’s incredible insight was to try to bring these two poorly connected fields together to create a textbook for college students called Molecular Biology of the Cell. It turned out to be an extremely difficult task, requiring that the authors spend more than a year of 12-hour days from 1978 to 1982 at periodic “book meetings.” The result proved to be valuable to scientists, even though designed as a textbook for students. Our textbooks, in 12 editions to date that include a lower-level version, Essential Cell Biology, have really made a substantial difference in attracting young people all around the world—from Russia to India to Brazil—to become interested in science. I think that’s been my major contribution to education.

PO: Why are you an NCSE member?

BA: I don’t remember exactly when I joined NCSE. But when I was at the National Academy of Sciences, we were very much aware of threats to science in various states. I was deeply involved in producing materials that would be useful as resources for scientists when they went before state school boards and state legislators. [Former NCSE Executive Director] Genie Scott was very visible. She came around the Academy often, and she gave impressive talks at many meetings that I attended. NCSE was doing very important work aligned with our Academy efforts and I was very aware of what the organization was doing to support accurate science education standards.

If people don’t know what science is, and they hate it because of how they were taught in middle school or high school, then they have no reason to believe what scientists have to say. And it’s not just when it comes to evolution, but about rational thinking, too, and respect for science judgment. It’s important to get the public to understand the nature of science and that scientific judgments are different than dogmatic judgments. NCSE can move us all—including scientists—to think in more sophisticated ways.

A version of this post originally appeared in Reports of the National Center for Science Education 39(3). If you like this interview, you're going to love the whole issue.